Book Review-Bowling Alone

Picking up a 14-year-old book on social trends seems like a foolish thing to do in the world of the Intranet. It seems like with each new month that passes there’s a new definition of social at Internet speed – however, social is, as my friend Eric Shupps comments, “with beer in hand.” Whether you share Eric’s appreciation for alcohol or not, the comment is correct. Social isn’t about microblogging, a new Facebook game, or technology – social is, at its heart, about people. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, Robert Putnam’s book about the decline of social capital in America, has been quoted in several of the books that I’ve read recently. It was quoted in The Science of Trust and Theory U. When multiple sources start pointing back to the same source I know I have to read it. There’s something there that a quick mention will miss. It starts with social capital.

Defining Social Capital

Before getting into the details of the decline of social capital in America and what causes it, we first must understand what we mean by social capital. Social capital is the idea that social networks have value. We inherently know this when we or someone we know is looking for a job. Social networks are the relationships – of varying strengths that we have. The more people we have relationships with – and the deeper those relationships — the more social capital we have.

Ultimately, our relationships with one another convey an ability to trust. We are, as Building Trust says, more likely to trust those who are more familiar to us. Trust is a lubricator of economies. It reduces the friction with which you enter agreements. That reduced friction means that you’ll go farther. Trusting is one of those powerful root virtues that in our daily lives we often overlook. (If you’re interest more in trust and how it works you should see my post Trust=>Vulnerability=>Intimacy.)

Trust is more than just our direct trust of a singular person. It becomes woven into the fabric of our environment. This happens whether we believe in Karma – or not. We see that people get what they deserve – or not. As a result, our economies and our communities flourish – or wither. The Science of Trust speaks about the difference in strategies in different games. For instance, in games when coordinating efforts isn’t an option, the tit-for-tat strategy is often best – in short, Karma works. However, if we all do just what is best for us (von Neumann-Morgenstern equilibrium), we don’t truly end up with the best results. The best results come with a Nash equilibrium where we all work for everyone’s best interests – certainly our own, but others as well. That’s what social capital does. It shifts us from focusing only on ourselves to focusing on everyone being better off.

Membership Has Its Costs

While membership may have its privileges, it has its costs as well. In the case of American Express, it’s the annual fee. In the case of most organizational memberships today, it’s a membership fee. Whether it’s Aircraft Owners and Pilots’ Association (AOPA), the National Rifle Association (NRA), or the World Wildlife Federation (WWF) membership means paying a fee. However, this isn’t the same as it was for our parents. When they joined the Rotary club, Kiwanis, Lions, Elk, or Moose they knew they were making a commitment to spend time to invest in building social capital with the rest of the club.

Over the years, we’ve traded our personal involvement with groups and the causes they’re working on with a check. In turn, they’re working on advocacy and lobbying in Washington, DC. Instead of personally gathering to commiserate with others who share our goals and values, we’ve delegating those responsibilities to professionals who are tasked with moving forward our perceived objectives. This transformation to a financial relationship has allowed organizations to grow – and shrink – rapidly. Generating membership means little more than running mass marketing campaigns – but once those campaigns are complete, membership doesn’t typically stick – because there is very little social capital or relationship holding the membership to the group. People simply don’t identify themselves as members of Greenpeace like they did the Moose or Elk.

The problem is that social capital is formed on relationships and shared identity – not on money given to a cause. Social capital which drives society forward doesn’t work by proxy. You can’t learn to trust the folks in your neighborhood or community if you never work with them for goals that you both find important.

Considering the Church

Bowling Alone breaks groups into community, church, and work-based groups. In this division there’s plenty of evidence that church groups are the most likely group to perform philanthropic activities. In fact, the strongest indicator of philanthropic activity is involvement in church. So churches have an important role to play in the development of the fabric of society – even if the bonds of social capital are fraying at their edges.

Churches today are facing their own crisis. I wrote a bit about this crisis in my review of Churchless. Churches simply aren’t drawing the same number of people as they used to. Church attendance is certainly lower than it was 40 years ago. Despite the efforts to engage people and draw them back to God, the battle is being lost. Churches simply aren’t immune to the factors that are unraveling social capital development.

Collaboration, Competition, and the Employment “Contract”

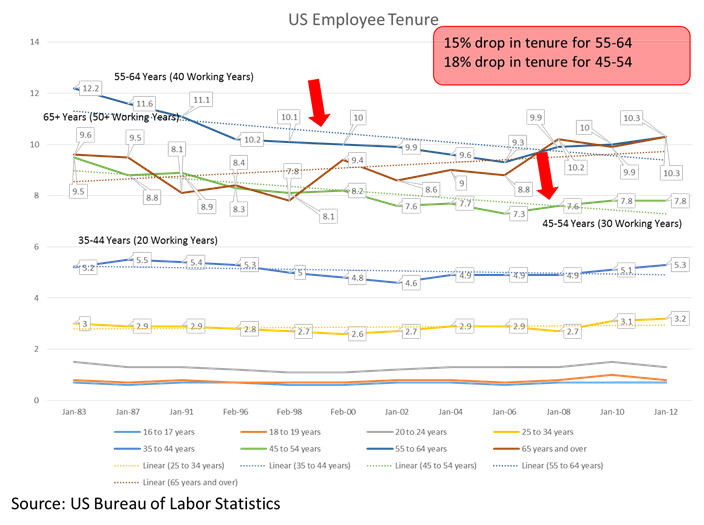

We learned in Collaborative Intelligence that competition inside a group is a bad thing. We also learned from Hackman that he believes that the setup of the situation can be as much as 60% of the outcome. The setup can be a part of the social contract – or the social norms – that we all expect. It used to be that people expected to work their entire careers for one organization. When you started at General Motors or IBM or wherever, you expected that you would have a job with them until you retire. However, the corporate restructuring and downsizing in the 1980s meant that the implied social contract of employment for life was broken, and along with it came waves of change.

The number of people who HAD to find a new job (involuntary turnover) climbed, but so too did the people that chose to find a new job (voluntary turnover). In the exchange we were left with a more mobile workforce. Though the Bureau of Labor Statistics numbers don’t show a substantial change in job tenure over the last thirty years, there is a change. Even the small changes we’re seeing may be the tipping point between feeling secure and feeling insecure. Or perhaps just the press coverage that there is a change in tenure has created a feeling of insecurity.

When you don’t feel secure that you’ll have a job for the long term, your attitudes, behaviors, and perspectives change. Instead of helping a coworker be more effective at their job you’re more likely to focus on your own work and avoid helping them. If you believe that at the end of the day it will either be your job or theirs that is eliminated, as much as you like them, you’ll hope it’s their job eliminated and not yours. That means that instead of collaborating and supporting them you’re now competing with them – and that’s a bad thing.

Communities that Heal

Communities, as we learned in Change or Die, can have a healing effect. Tight knit communities support and watch over one another. They form associations to make micro loans when banks won’t make them. They watch – and discipline — each other’s children. These are the kind of communities that we want to be in – but also that are becoming rarer. We’re becoming increasingly more insular as we sit inside our air-conditioned houses instead of on the front porch. We don’t say hello to the neighbor as we get out of our car because we pull into our garage with the automatic door opener – which doubles as an automatic door closer. The logistics of our lives have us interacting with neighbors and their children less.

It’s hard to be involved in a tight knit community when you aren’t exposed to it. We’re also falling victim to another major trend – the trend of valuing our independence. As Americans, we own more cars and drive further than any other nation. We have a strong belief about the value of independence. No longer do we live in small agricultural communities where people came together to build barns support those who had hardships. Instead we are in the hustle and bustle of our industrialized and individualized lives. The communities that we grew up in where everyone knew your business are no more – because we have decided that we aren’t interested in being interdependent upon each other – because we’ve become more self-reliant (as Emerson would say).

Building Trust in an Electronic World

The reality today is that we’re living in an electronic world. We don’t get the newspaper any longer, we logon to CNN. We don’t watch the weather, we login to weather.com. We used to trust in institutions like companies. We used to trust in the government. We used to trust in each other. We can no longer see the micro-expressions that require a 60th of a second to see. Trust – it seems – is under assault. Our ability to dissatisfaction and alienation has risen in tandem with social media. We don’t trust institutions. We’ve seen church leaders do horrific things. We’ve seen banks and institutions of all types fail.

I described in my post Building Trust: Make, Renegotiate, Meet that the recipe for building trust isn’t hard. It does, however, take a long time. You have to meet many commitments before someone will trust you. Consider Ebay, which relies on feedback from other people to help you trust that the person with whom you’re going to complete a transaction is safe to work with. You rely upon that person having made and met commitments with other parts of the community.

Work If You Want To

One of the hypothesis presented about the decline in social engagement was that the primary drivers of social capital, wives of working men, started to go to work themselves and, because of that, they became less engaged in social clubs. However, the data doesn’t seem to support this hypothesis. Quite the contrary, that when people were working part time – particularly because of desire to work – there was a rise in the amount of volunteer and social work being done. In other words, getting women out of the role of homemaker may have some negative impacts on social capital development, but it has just as many, or more, positive impacts.

So yes, people are busier, but they’re also more engaged through the process. Working part time seems to drive social capital creation rather than deter it.

Wartime Activity

We, collectively, have more free time now than at any other point in human history. We spend less time working for our basic needs than at any other time. We are enjoying our time. That is, we’re enjoying our time until we’re rallied to a cause. The cause drives us to be more productive and turn away from the unimportant things. We found war twice in the 20th century. These were times when we in America rallied against a common enemy – and as a result we gave up some of our leisure time and instead focused on productivity.

However, what happened when the war was over and it had been won? Much has been written about the plight of veterans returning from war – but is it broader than that? Is it that the entire society was trying to readjust and cope – and the result was that we created more productive activity for ourselves? That is, that we decided for a brief period after the war – after the struggle – that we wanted to create in the world a better place and that we were willing to continue our activity level to be able to get it? It seems like this may be plausible based on the data, which indicated that the social capital creation increased at end of the war – at least for a short time. After a few years this engagement wavered and we started a downward spiral.

Social Norms of Connectedness

How often should you call your parents? How about your siblings? What is a normal level of connectivity with your family? How about your friends? These are hard questions with no single answers. The answers are driven by what your social network believes the right answer is. You may have friends who speak with their parents weekly – or even daily. You may call much less frequently, monthly or quarterly.

Slowly, and perhaps imperceptibly to us in the moment, our norms of social connectedness have changed. We moved away from our childhood homes and cities. In the era of long distance phone call rates we didn’t call each other as often because of the cost. Along the way we developed new habits – new norms – of connectivity. We’re changing the way that we’re connecting. It’s through Facebook and social media – and the data seems to point to the fact that social media isn’t the same as social gatherings. We’ve established new social norms, but they may not be healthy for us personally (we’re more stressed and anxious) or for society.

Bowling Leagues

Crowding inside a bowling hall breathing smoke filled air, drinking to excess, and eating high-fat, high-calorie foods may be the healthiest thing you can do – if you’re forming relationships with the people that you’re bowling with. Sure there may be the occasional heart attack caused by the food, but as it turns out (and as I’ve mentioned in my review of Emotional Intelligence.) the deep social connections that you’re building at the same time have an immense impact on your overall health. You’re better off drinking a beer and eating a greasy pizza with your best friend at a bowling alley than staying home and being isolated. It turns out that as we’re losing our social capital we’re also losing our health.

Social Capacity and Facebook as a Brain Augmentation System

A British anthropologist Robin Dunbar observed that the size of social groups increased with the size of a mammal’s brain. This led to what is called Dunbar’s number for humans, which places the number of stable social connections that we can maintain at about 150. If you’ve been on Facebook or LinkedIn for a while you’re likely to have more than 150 friends – or connections. However, Dunbar was speaking about a different level of connectedness than we’re used to today. He was speaking about communities of people. He was talking about social grooming – the process whereby we support each other and help each other survive.

In truth, Dunbar’s research really lead him to believe in different rings of relationships, each of which had a different level of trust. In the wider circles Facebook is effective at keeping us loosely connected with others that we’ve become acquainted with. It turns out that Facebook (and LinkedIn) becomes a way to help us maintain relationships in this outer circle of acquaintances, but it isn’t the same as having deep social connections with our list of Facebook friends.

The Causes

So what is the cause of the drop in social engagement? Who is holding the smoking gun of social malaise? The answer, as it turns out is that it appears to have been a set of factors (a conspiracy, if you are prone to such theories). No one cause can be found. While there are some factors that clearly have had a larger impact than others, there’s no way to single out a single cause. However, here are some of the suspects that the book lays out – and their associated crimes.

Television

Of the causes for the decline in social engagement, none was found to be more powerful than the invention of the television. The television privatized leisure time. One can sit at home in front of a television and be entertained with no effort of their own. Television is, quite simply, a very low-effort way to find pleasure. However, much like eating only chips all day would leave us longing for something more – something more solid, so too does excessive television watching. It’s the leisure equivalent of filling up on junk food. It tastes good going down but the longer term effects in our overall mood – and our waistline – are not desirable.

The data says that television is singularly the leisure activity that inhibits other leisure activities. Every other leisure activity led – statistically speaking – to other forms of leisure. Television doesn’t. Once your mind gets sucked into the television it’s unlikely to come out to play with others. Of all of the causes that Putnam evaluated, it was television that had the highest probability of contributing to the decline.

Generations

The second highest correlation came from a look at the various generations and their dispositions towards social capital creation. It turns out that, from voting rates to memberships, the declines seem to come in part from older generations disappearing from active social life. These folks have put well more than their share into our social capital development. They’re simply no longer able to continue to invest and the younger generations aren’t picking up the slack.

The older generations are still holding their own – being more involved during retirement than they may have been while they were working. They’re doing all they can into the golden years of their life but at some point no longer have the capacity to help.

Garage Door Openers

The final suspect is my suspect. It’s that we’ve become a garage door world. We drive home to our houses and we don’t park our cars outside where we can have the serendipitous conversation with our neighbor to learn about how they’re doing or the social concern they care about. We don’t spend time tending our lawns and gardens like we once did to create accidental engagement with others. We go inside and sit in front of the TV or the internet without needing – or wanting – to interact with anyone else in our neighborhood.

There’s no good measure for engagement in our neighborhoods. There’s no count of random interactions with our neighbors, but my personal observation is that, now that we don’t park our cars on the street or in the driveway as much, we simply don’t have as many random interactions.

Timeless and Timely

If you’re serious about social capital in your community, or even if you’re just serious about making social enterprise in your organization using only electrons, you should pick up Bowling Alone so you can understand the mechanics and the history of social in America.