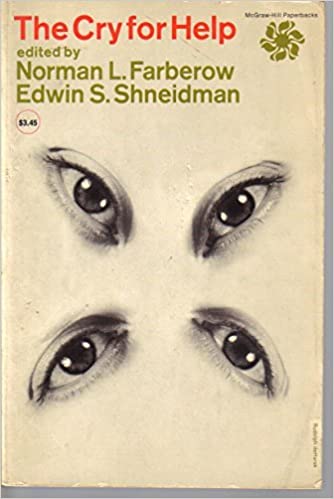

Book Review-The Cry for Help

One of the things that people often say about those who attempt suicide is that it’s just a cry for help. While this isn’t true – every attempt should be taken seriously – The Cry for Help covers suicide attempts and death by suicide as it was known in 1965. It was a time of serious condemnation for those who attempted or died by suicide. Society was even quicker to blame parents, siblings, and spouses for a death by suicide – or an attempt – than today.

The Presuicidal Phase

As Joiner points out in Myths about Suicide, you can’t tell who will die by suicide by looking at them. There aren’t tell-tale signs that anyone can pick up. Joiner’s position (at the time of that writing) was that there are signs that predate a suicide attempt. He challenges the research with attempters that they hadn’t considered suicide more than a few hours before their attempt. The challenge – a fair one – is that attempters and those who die by suicide are an overlapping but distinct group.

Increasingly more research is added to the pile that, while some people who die by suicide have a presuicidal phase where they’re considering it and sending signals, some do not. The latest research puts well over 50% of people not considering suicide prior to a few hours before the attempt. That research wasn’t available in 1965 so the perspective is one where all suicides have a presuicidal phase with detectable signals that suicide is eminent.

Our experience today with the predictability of screening and assessment tools shows the same challenges. We simply can’t use these tools to predict who will attempt suicide or not.

To add further challenge is the fact that even if signals are sent, they may be too low to be detected. They may fall into the category of normal variations that people don’t detect. Behavior changes are often cited as a suicidal signal; however, people change their behaviors every day in a variety of ways based on reasons to numerous to count. Thankfully, few people who change their behaviors are truly suicidal.

Should we ask people if they’re going to harm themselves or attempt suicide? Absolutely. However, that isn’t to say that we’ve got to develop absolute prediction skills.

Suicidal or Accidental

The coroner’s job in determining what is – and what is not – a suicide is a challenging one to say the least. There are some situations that are clear cut, but many more where it’s not possible to peer into someone’s intent after the fact. This is why Shneidman started working with the coroner to help tease out the difference between accident and suicide. (See Assessment and Prediction of Suicide.) Even with advanced techniques for interviewing those who knew the deceased, there are still many errors that can be made, such as whether the car that crashed into the tree slid on an icy road or whether the driver intentionally pointed the car at the tree.

We may never know whether some deaths were accidental or suicidal – but in the individual case that may not matter. It certainly will not bring them back. The value in the distinction lies in our ability to potentially prevent the suicide. However, as Bryan points out in Rethinking Suicide, suicides are like car crashes in that you can’t predict them at an individual level. Our goal is to make things safer and in that way we’ll reduce suicides.

Secondary Benefits of a Psychological Autopsy

If we can’t see with clarity someone’s intention, the process of gathering the information in the psychological autopsy may be beneficial as postvention to those left behind. Postvention is the process of caring for those left behind after a suicide. (See Suicide and Its Aftermath for more on postvention.) Many have reported that telling the story of their loved one is therapeutic.

The truth is that we need stories to make sense of our experiences. Rich Tedeschi explains in Transformed by Trauma that PTSD is really our inability to process something we’ve seen or done. By helping the family members formulate their story about their loved one, they get a chance to process the experience. This is similar to the techniques that are explored in Opening Up and The Body Keeps the Score where the story process is encouraged.

Irredeemable

In some cases, the underlying drivers for suicide may be an unshakable sense of shame. That is, it’s not that something that they did was bad (resulting in guilt) but rather that they are bad. This sense of shame may be persistent if the person believes that they’re irredeemable. The sense that everyone can be saved from their current state – no matter how bad – creates the window for hope to hold on and to keep people trying to find ways to better themselves – and survive.

No one is irredeemable. Don’t let The Cry for Help go unheard or unaddressed.