Now Available: Organizational Readiness for Generative AI Draft White Paper

Book Review-Stay: A History of Suicide and the Philosophies Against It

I’ve never met a suicide survivor who wanted to congratulate the person they lost on a great decision. Universally, the word that they wanted to tell them was “Stay.” That’s why Stay: A History of Suicide and Philosophies Against It was so interesting. What has history said about suicide and its acceptability to society?

Jennifer Hecht, who also wrote Doubt, starts by recounting a few of the influential people in her life whom she’s lost and some of the impact on her. She longingly calls out to the people she’s lost to stay.

Suffering

I firmly believe that people who die by suicide are dealing with pain. Whether it’s physical pain or the psychological pain that Shneidman called “psychache,” there’s something that makes death look more appealing than life. (See The Suicidal Mind for more on psychache.) I also believe that the best way we have of ensuring people do stay is to give them hope and reduce their pain. (See The Psychology of Hope for more on what hope is and how to generate it.) While reducing pain is individualized, there is a commonality in that changes don’t always need to be objective to make a difference. Sometimes, just seeing things differently is enough.

Hecht starts with, “Suffer here with us instead.” I struggle with that perspective, because it necessarily puts the requestor in the position of contributing to the hurt of another person. That’s not to say that it’s necessary harmful in the long-term sense. (See Hurt, Hurting, Hurtful for clarity on hurting.) However, there’s also a sense of one up-one down. (See Compelled to Control for more on one-up one-down.) The person making the statement is necessarily saying they know better than the person themselves what is best for them. As Motivational Interviewing points out, this isn’t a good position to be in. (See also A Way of Being.)

The rest of the statement is, “We need you with us, we have not forgotten you, you are our hero. Stay.” While I think that it’s a bit overstated, it’s a positive affirming statement about how much you want the person to continue to live. However, the hyperbole of “hero” may cause someone to challenge the statement.

Future Selves

What we know about pain, stress, and suicide is that they cause people to focus on the current moment. They may be hopeless because they see no way out of their current pain – even if there are viable options. While Hecht calls the suicidal person to consider their future self who may want to live, her grief at her losses blinds her to the research that indicates, in the moment of passion, no one is going to be able to see their future selves.

One could say that they could have this argument preloaded into their thought processes, so that when the crisis arises, they’re prepared. However, without some sort of a prompt, this, too, may be difficult to operationalize in the mind of the person struggling.

Collateral Damage

Another rational plea that is often used is that the person who is considering suicide think about how others will react to their death. The first barrier is that they have the same perception as others, and that they don’t believe they’re a burden. (See Thomas Joiner’s in Why People Die By Suicide.) The second barrier is back to the constriction that prevents them from seeing anything but their current pain and the absolute desire to stop it.

Some say that suicide transfers the pain of the person who dies to their loved ones. (See Suicide and Its Aftermath.) And while this statement is not literally true, it’s both figuratively true and irrelevant. The person who is struggling to live can’t see how their death will harm others.

Pain as the Path

Another argument is that the person should endure the pain, because it’s the pathway to wisdom. While this may be true, it may not be enough. We’re wired to make sense of the world, including the tragedies we face. (See Trauma and Memory.) However, when the pain becomes too severe, this is little solace. Some will say that which doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. However, as Antifragile explains, that’s not truth. There are bands of strain and challenge that can help you grow – but there are also levels of struggle that do nothing more than harm you and beat you down.

If we’re supporting someone with suicidal ideation our goal should be to ensure that their pain is minimized to a level where it can create growth. (See Posttraumatic Growth for more.)

Hold Your Ground

Plato suggested that we are assigned guard posts, which we should attend until we are dismissed. To die by suicide is to abandon our post and leave our community vulnerable. The general principle is that we’re responsible to the community and choosing the time of our own death deprives the rest of the community of our life.

While this is a sound argument for the person making a determined decision to die by suicide, it won’t dissuade the impulsive person from dying by suicide.

Christian Suicide

Christianity has a problem with suicide. Given Saul and Samson both in the Old Testament as well as Judas in the New Testament, suicide is both mentioned in the Bible and also not condemned. Even Jesus’ death on the cross was one that he could have avoided. The language is that he gave up his life – an active choice. That means or at least implies suicide. It’s no surprise, then, that early Christianity had no problem with suicide – particularly for martyrs.

Then the Church started shifting away from suicide being acceptable. Through scholars and meetings, suicide became gradually less acceptable until it was outlawed, and those who died by suicide couldn’t be buried in the church graveyards. Those who attempted but lived would be excommunicated. It’s only in very recent times that the Church has accepted that people who die by suicide aren’t evil.

While suicide isn’t accepted by the Church, the prohibitions for the normal rites of burial are no longer denied. The Church accepts it like they accept sin. They don’t like it, but they accept that it’s impossible to prevent.

Islam

Islam’s position on suicide hasn’t changed much. Islam prizes people who endure unbearable lives. Suicide is therefore abandoning one’s opportunity to be honored and praised. The specific rules regarding the disposition of bodies of those who died by suicide may vary from sect to sect, but the general disdain does not.

Dramatic Tragedy

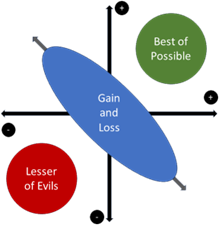

There are multiple historical accounts where suicides could have been prevented if only we were more patient. Marc Anthony thought Cleopatra was dead and therefore killed himself – and she killed herself upon discovering Marc Anthony’s death. Had Romeo waited just a few more minutes, he would have seen that Juliet was still alive and desperately committed to him. This forms the historical foundation of the aforementioned future selves argument. Suicide is – as Phil Donahue said – “a permanent solution to a temporary problem.” (See also Choosing to Live for permanent solution to a temporary problem.) It cannot be undone.

From a prevention standpoint, we know that any time we put between a person and their chosen means reduces suicidal outcomes. Suicidal crises – when people are willing and able to complete the act – are, relatively speaking, brief. (See Alternatives to Suicide for more on suicidal crises.) If someone can be helped or delayed in these moments, their chances of ultimate survival are quite good.

Third-Party Suicide

Since suicide was prohibited but being executed was not, many people got creative. Women would commit murder to be sentenced to death. That was until a law was enacted requiring that a person receive life imprisonment if they killed someone just to be killed. Men would sometimes falsely claim bestiality, since that was a capital offense. We know that these approaches were used from records.

In more recent times, it’s more common to see suicide by cop. That is, a person creates a situation where police have no choice but to shoot and kill the person. Often, this is because they’re brandishing a weapon or threatening others. (See People in Crisis for more on suicide by cop.)

Our Own Dungeons

Some may believe that they’re their own dungeons. They believe their bodies or their circumstances have trapped them. In my review of The Neuroscience of Suicidal Behavior, I acknowledged that there’s no telling what a trapped animal will do – including the human animal. When trapped, animals and humans are willing to do anything to escape. In my review of When It Is Darkest, I explained that, sometimes, being trapped is only in their mind – but that doesn’t mean it’s not real to them. Viktor Frankl in Man’s Search for Meaning sheds light on how the external circumstances could be the same – a prisoner in a death camp – but individuals can respond very differently.

John Milton in Paradise Lost said, “The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven.” If we want to help people stay, we need to simultaneously acknowledge and accept the way that they see the world and try to influence them in ways that turn a hell into heaven – rather than vice-versa.

It’s possible for a body to feel as if it’s imprisoning us when infirmities come upon us. However, research shows that the mood of accident victims who become paralyzed will likely return to a baseline after a few years. None of us have perfect or ideal situations, but there’s often some good in any situation. If we can gently guide people to it, we can help them be more positive.

Life Worth Living

In the end, rather than imploring people to stay, we should focus on helping them find that their life is worth living. If they can find passion and purpose, then they’ve got a chance. If they can develop a habit of service, they’ll realize that the world needs them. If they can see the positives of their experiences, then maybe they won’t have to be asked to stay. Maybe they will want to Stay.