Robert Bogue

March 22, 2024

No Comments

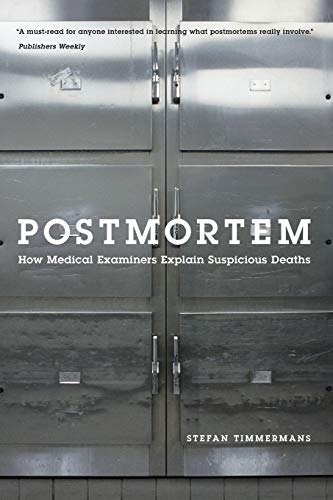

It’s not a morbid curiosity (or maybe it is). One of the key aspects of suicide work is the psychological autopsy or fatality review. It’s an attempt to understand the intent of someone who died to determine whether their death was an accident – or if it was intentional. If I was going to understand the psychological autopsy, I felt I needed to understand how the overall autopsy process worked, which led me to Postmortem: How Medical Examiners Explain Suspicious Deaths.

It starts with an understanding that, even though it’s performed postmortem (after death), it’s done for the living. It helps us to better understand what happened and what things can cause death. Autopsies are at the heart of much of our medical knowledge. What’s curious is when the long-term or justice needs served by an autopsy come in conflict with the short-term, organ-donation, life-saving benefits. The ethical dilemmas are large in a space where we’re seeking the truth by means of dissection.

Suspicion

Now, autopsies are done only when the death is suspicious, “suspicious” meaning the death occurred out of place or out of time. Perhaps the person was found two states away from where they lived. Maybe they died young without any known diseases. Maybe the scene of their death just didn’t look or feel right. (See Sources of Power about unconscious, tacit knowledge that can lead to “not right” without the ability to articulate why.)

Overall, roughly 75% of deaths occur in places where they’re expected. Nursing homes and hospitals have staff that understand how to be culturally sensitive in response to a death. While it is not the desired outcome, it is one that they’re all too familiar with. Of the remaining 25%, most (20% of all deaths) are suspicious. Those are the ones that consume the medical examiner’s attention.

Hope

The kind of hope that fills the medical examiner isn’t going to help the deceased. If they discover an infection, it can be that it may help prevent its spread or aid in its identification. They can save other lives by means of advancing medicine and public health initiatives. However, a different situation reveals a homicide rather than a natural disease.

In the case of homicide, the medical examiner serves the public good by increasing the chances of finding and punishing the offender. This frequently removes them from the general population, thus preventing another homicide. Additionally, the belief that, if you murder another individual, you’ll be brought to justice deters the action. (See Dreamland for the power of deterrent.)

Expert Testimony Standards

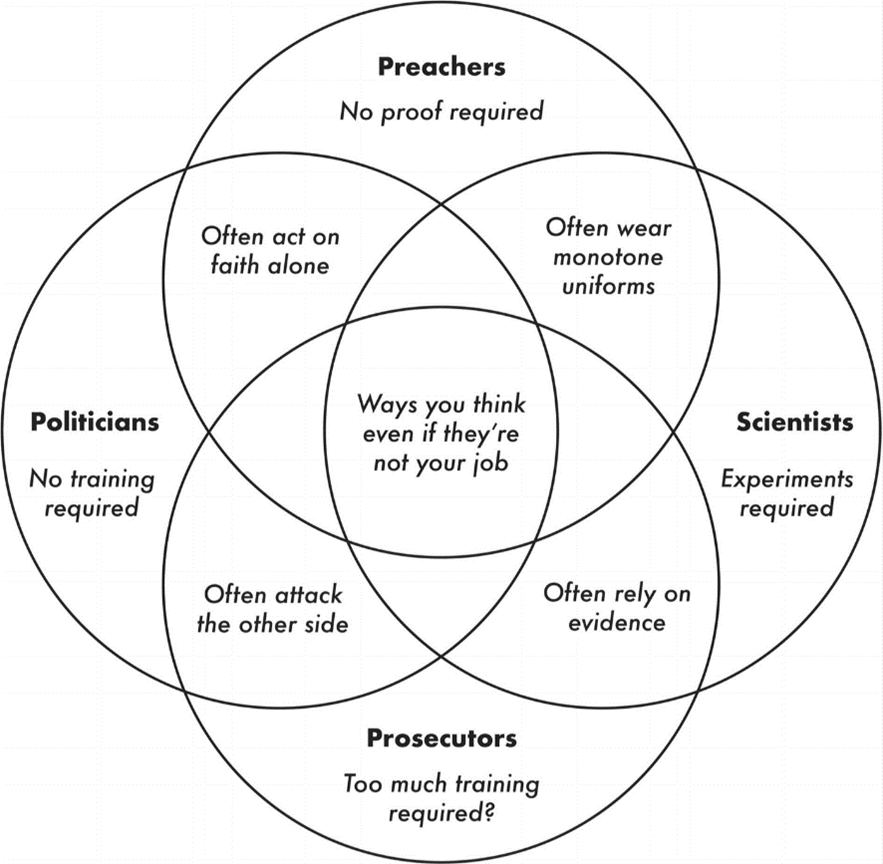

Ultimately, if a medical examiner determines that a person was murdered, they’ll be called to trial. During the trial, the medical examiner will be called as an expert witness. A series of court decisions collectively known as Daubert-Joiner-Kumho establish the criteria upon which a judge can disqualify a witness as an expert witness. I cover the criteria in detail in my post for Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology, and in my review of The Cult of Personality Testing, I explain how Rorschach’s inkblots fail to meet this test.

It’s for these reasons that the approaches medical examiners use are exacting and why their documentation is rigorous. They want to ensure that their testimony stands up to the judge’s criteria – and ultimately cross-examination. The cross-examination represents a bigger problem, because no matter how high the standards are in a medical examiner’s office, there are always more things that can be done; it’s important to help the jury understand that the steps that aren’t done don’t add enough value.

NASHU Standard

For the most part, medical examiners use a standard for the manner of death. NASHU stands for Natural, Accidental, Suicide, Homicide, or Undetermined. Buried in this is the problem of inferring intent. Did the person intend to run off the road into the abutment, or did they lose control of their vehicle? One is an accident, and the other is a suicide. Did the mechanic intentionally disable the brakes on the vehicle, or did they simply fail? One is a homicide, and the other is an accident.

Hiding Intent

A bullet wound is relatively easy to document and implicates a gun as the method of death. However, it says nothing for the manner of death – it says nothing for intent. Was it an accidental discharge while cleaning the gun? Was it an attempt to die by suicide? Did someone else fire the gun?

Some medical examiners had previously only recorded the manner of death as a suicide if there was a suicide note. However, this substantially undercounted the number of suicides, because the rate of suicide notes for death by suicide is quite low. (See Clues to Suicide.) In many cases, the person dying by suicide intentionally hid their intent – at least prior to their death – to prevent people from trying to stop them.

Similarly, murderers have substantial motivation to hide their behaviors, so the medical examiner might classify the death as natural or accidental – or at least undetermined. So, while intent is difficult to discover, it’s the job of the medical examiner to use all the medical tools at their disposal to expose the method and manner of death.

Thanatography

A biography is the story of the living. It’s the story of their life. A thanatography is a story – or narrative – of the death. If those around the deceased volunteer the social situation for the individual, it may include their losses and environmental problems, but frequently it does not. Think about the impact on intent if the deceased recently lost a job or a love or had financial or legal problems. It creates significant doubt that their death was either natural or accidental – though these same factors would tend to create poorer cognitive processing and therefore poorer decision-making, potentially leading to an accident.

Things We Do

Disturbing a dead body is taboo in Western societies, which is why there is a degree of concern about the autopsy process. However, we accept it as a necessary process to protect the public interest. We do many things in an attempt to save patients, which make the medical examiner’s job harder. Life-saving attempts like CPR have successful recovery rates in the single digits and necessarily create their own traumas. When it’s not successful, the medical examiner is forced to decide whether the injuries they see were causal to the death or were a part of the attempts to retain life. (Most people don’t realize how much force must be used to do CPR correctly.)

Addiction over Intent

With addictive substances, like alcohol, the precipitating causes of death are presumed to be overdoses rather than suicide. The presumption is that the factors that would lead to an accident are stronger than their agency to produce a suicide. (See The Mind Club for more about agency.) In cases of overdose, it’s rare that the evidence can outweigh the bias towards an accident. Certainly, a suicide note is clear but, other, subtle signs of distress may justify the increased substance use as a way of numbing.

Medical examiners are used to this kind of precedence in general, with cardiac (heart) causes taking precedence over pneumology (lungs). Immediate, lethal trauma has precedence over chronic disease. In this way, there’s an order to the evaluation of criteria.

Validity of Precision

The documentation process can consume 75% of the work of the medical examiner because of its criticality to the potential legal needs – whether defending the office or prosecuting a murderer. In this documentation, accuracy is privileged over precision. Bands of gold on the left hand of the victim will be described as such even if it’s clear to everyone that it’s a wedding ring. The first is an observation. The second is a culturally-informed value judgement – and is thus less about truth and more about the beliefs of the examiner.

Witnesses

The history of law has a long relationship with witnesses both in recognizing their necessity and their lack of reliability. In numerous places, the Christian Bible explains the need for two witnesses – including Deuteronomy 19:15. The implication is false accusations, but there’s more than that. Witnesses are notoriously unreliable owing to our belief that our memories – and theirs – are accurate representations, like a photograph or a video tape. However, we know quite clearly that our memories are more reconstructions than they are recordings of the actual events. (See White Bears and Other Unwanted Thoughts.)

It’s a difficult spot for prosecutors when the memories of the witnesses come in direct conflict with the pathological evidence that’s captured by the medical examiner. Simple changes like believing a person was stabbed in their left or right side when the physical evidence shows the opposite can unwind the credibility of a witness’s testimony.

Getting Away with Murder

While precautions are taken to prevent someone from a murder going undetected, not everything in the autopsy process is biased towards detection. Precautions like delaying examination for 24 hours and limiting the toxicology screenings to the things that make the most sense mean that some mechanisms for murder can slip past detection. Some substances break down in the 24-hour period and aren’t detectable. Others are sufficiently rare that they’re rarely tested for.

Medical examiners noted that the homicides they saw tended to be of the “heat of passion” kind. These murders aren’t well planned out and are thus relatively easy to spot. Of course, if someone had planned out a murder well, the medical examiners would reach the same conclusion – leaving the well-planned and executed to accidents, natural, or undetermined, because there were no traces of evidence left. Either way, the chances of getting caught taking someone else’s life are sufficiently high as to be a deterrent.

Police Homicide

Invariably, there will be a requirement for a medical examiner to evaluate a death caused by a police officer. Some cases will be where the suspect forced the officer into a decision to shoot. It’s possible that some of these are best described as suicide by cop, where the victim wanted to die but couldn’t do it themselves, so they created a situation of threat that no officer could ignore.

Other cases are tragically where the officer used too much force for no valid reason. The problem, for the medical examiner, is that the bias to not declare the officer – whom they’ve worked with for years – as the problem is large. It’s a very high bar for a medical examiner to determine that the officer used a level of force that resulted in death because of the discomfort they’ll feel in doing so.

When Babies Die

In the second half of the nineteenth century, historians estimate that 15-to-30 percent of infants didn’t live to their first birthday. It’s difficult to attach to a baby that you believe only has a 3:4 chance of living. By attaching, you’re setting yourself up for a high degree of loss. In today’s world, infant mortality is substantially lower. That’s why, when a parent or caretaker doesn’t show sufficient concern for the death, they’re automatically considered as a suspect. There’s a cultural norm to grieving even if it’s a unique experience. Reactions outside the normal, expected band are suspicious.

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is a real problem that plagues infant mortality. In 2002, about 8 percent of infant deaths were attributed to SIDS. Some of those undoubtedly weren’t SIDS in the proper sense. Some of them are situations where babies are suffocated – mostly accidentally. One Ohio coroner observed wryly that “the only difference between SIDS and a suffocation is a confession.” Co-sleeping relationships, while understandable, place the baby at risk.

The Cost of Life

Organ donation saves lives. They’re frequently called “gifts of life;” however, they’re also big business. Technically, the organs themselves are gifts, but recipients are still expected to pay for the services necessary to get them. Sometimes, the needs of the medical examiner – including the 24-hour delay before examining a body and the potential desire to biopsy or cut open an organ to learn more – comes at odds with these life-saving goals.

There are no easy answers to what should take precedence – the harvesting of organs and both the lives saved and the economic engine it entails may be the right answer. Conversely, the need to protect the public from murderers has some lifesaving value, too. Which one should take precedence is a question that is becoming more legislated, with laws being written about who has precedence and when. This is necessary, because in some cases, medical examiners have failed to yield their presumptive authority for the preservation of life through organ donation.

It’s an ethical dilemma of the highest order, as it means life and death for different people. We’ll never know which decision was right, even Postmortem.