Book Review-The Simple Faith of Mister Rogers: Spiritual Insights from the World’s Most Beloved Neighbor

The actual source of my memory is lost to the sands of time. We lived in a few houses during the first few years of my life. I can remember seeing Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood – but I can’t remember which home I was at. I never knew Mister Rogers as a Presbyterian minister. What I missed in my early experiences was The Simple Faith of Mister Rogers: Spiritual Insights from the World’s Most Beloved Neighbor.

By Actions

There are only a few books that I remember where I was introduced to them. Heroic Leadership is one of those books. That plane ride and the simple Iowa woman who was studying seminary introduced me to a different way of Christianity. I’d grown up going to church, and I thought the only way to share Christ was through preaching. I learned what Saint Francis of Assisi already knew: “Preach the gospel at all times; if necessary, use words.” In other words, embody what it is like to be Christ (as best as a human can) and don’t worry about preaching, your actions will do that.

For millions of people, Fred Rogers was that: the embodiment of love and acceptance. Of course, no man is perfect, and his family could see his foibles and might see things differently. But, for the countless children who watched the show, there was a person who cared.

The Accuser or the Advocate

Both the accuser and the advocate expose problems. It’s not exposing the problems of the world that is inherently good or bad but rather what you do about it. Criticizing someone without a framework for how to make it better makes you the accuser. Even an inkling of how we might move forward and past the described limitations changes the conversation completely.

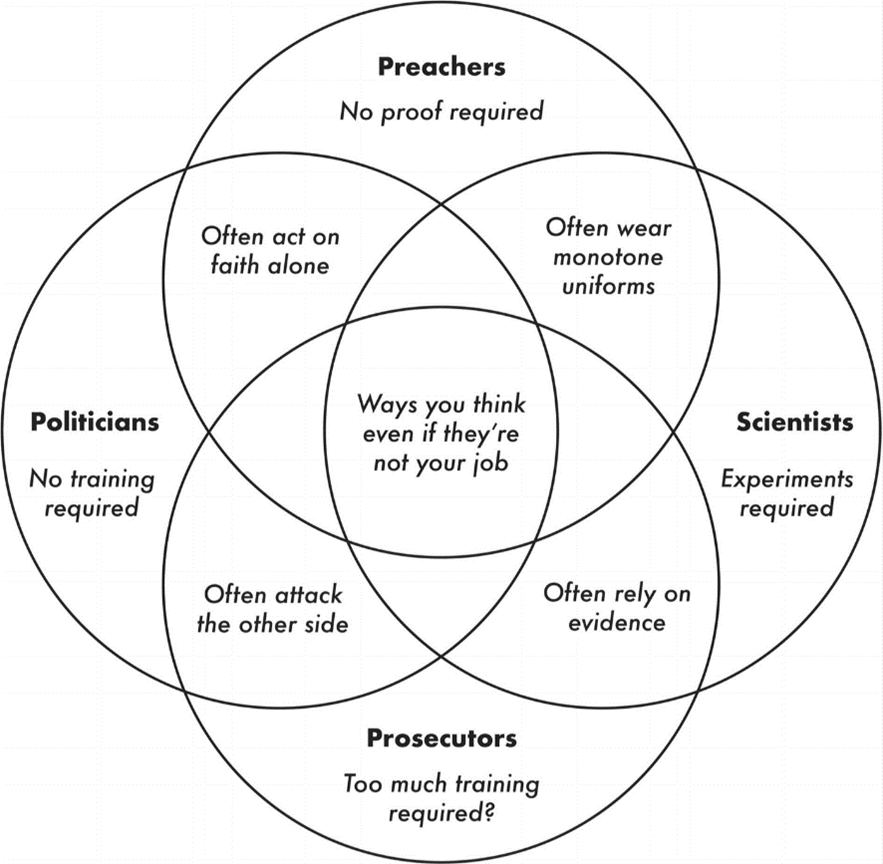

In Think Again, Adam Grant shares a framework from Phil Tetlock. (See Superforecasting for more of Tetlock’s great work.) The framework is of the preacher, the politician, the scientists, and the prosecutors. It’s best summarized by the graphic from Think Again:

The accuser, in Tetlock’s framework, is either the politician or the prosecutor – attacking the other side. In Grant’s view, the best person to be is the scientist. However, just because one is a scientist doesn’t stop someone from being appropriately critical of things that are wrong. Richard Feynman explains that sometimes this isn’t easy particularly when the error of another is considered fact. It’s a slow, painful process with many steps.

It’s appropriate to challenge the slow, measured, simplistic style of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood and expose the limitations – which led it to be what it is. Rogers was often criticized for his pace and focus on feelings, but Rogers kept leaning in on the research and trying to be an advocate for children even when others criticized him.

Hope

For a two-to-five year old (Rogers’ core audience) who didn’t have anything stable in their life, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood was an alien world. There wasn’t any yelling, fighting, throwing things, or even unpredictable anger. Fred Rogers lived his entire television life in one home. A child learning more about attachment bonds could see that stability was possible – even if it’s not possible in their circumstances. (See Attached for more on attachment.) This awareness could give them hope.

Rick Snyder in The Psychology of Hope says hope is a cognitive process that is built on two components. The first is waypower, or knowing how something could happen. The second is willpower, or the force to make the necessary changes. Often overlooked in this model is the truth that these both operate internally and externally. Seeing a world that existed without the day-to-day fear that some children were subjected to instilled hope in them by showing that other people knew how to create these environments.

Where Sesame Street was focused on intellectual learning, Rogers was focused on emotional learning. (See “G” is for Growing for more on Sesame Street.) Rogers knew that his work needed to be measured and clear so that young minds could absorb it. More importantly, he wanted to instill the ability to self-regulate emotions, which takes skills and the space to practice them.

Internalization

Deep into the research on attachment theory and secure attachment is a concept of internalization. It’s a concept where the people that you’ve lost leave imprints on you in such strong ways that you can continue to retain a relationship with them after they’re gone. For Rogers, this internalization included toast sticks. A kindly old neighbor in Latrobe would make him toast and cut it into sticks. One day not long before she died, she taught the five-year-old Rogers how to make the toast and cut them. He was able to take that new skill with him – and to think about her every time he made them.

We internalize people partly by what they teach us but also by learning how they would react to a situation. We can predict how they might behave whether they’re present or not. (See Mindreading for more on our predictive capacity.) This internalization allows us to become the best of the others that we encounter in life.

Space

The thing that Rogers created for himself and others was space. From the intentional, slow movement through the program to the routine that had him up every morning, he knew how easy it is to get distracted in a world full of noise. He inherently understood the value of reflection. (See Quiet for more.) While a television personality himself, he rarely watched television. Mostly, he preferred to read. Though he didn’t say it, in those days, television was live, which doesn’t create an opportunity to pause and reflect. Obviously, he had no inherent problem with television, it just wasn’t the way he chose to spend most of his time.

I’m not sure what Rogers would make of the ever-increasing pace that has come since his death. In the two decades since his passing, we’ve moved in ways that annihilate silence and venerate noise. Everything has been tweeted or turned into a TikTok reel. We can select our noise – as long as it’s not selecting silence.

Relationship

The essence of prayer is relationship. It’s a relationship with God. More specifically, the literal meaning of the language of prayer is the exchanging of worries for faith. We’re engaging in a relationship with a benevolent father, who takes on our worries and fears and responds with simple assurances that he is present. Relationships are built through talking. They’re built through sharing experiences. Relationships form on the basis of a desire to understand and on understanding. As we pray, we open ourselves up to relationships with God – and to hearing what God has to say.

Sometimes the person we’re relating to on Earth is a “cornball” – one of the ways that Rogers is described. We all have our quirks, and by all accounts, so did he. His idiosyncrasies left him slightly out of step with the world – in his case, perhaps in a way that endeared him to the children he sought to serve. Perhaps by demonstrating he wasn’t perfect, he made it a little easier for children who watched to accept their imperfections, too.

Feelings Matter

There’s a tendency to validate whether a fear is rational or reasonable given a set of circumstances. Our brains evaluate emotions and judge their validity in ourselves and others – and it’s not one of our better features. What feelings need is acceptance, not judgement. If we accept a feeling as real – irrespective of the reality – we can move forward towards working through or with the emotion.

Richard Lazarus in Emotion and Adaptation and Lisa Feldman Barrett in How Emotions Are Made help us to understand that there are cognitive processes, often operating below our conscious awareness, that are designed to keep us safe. Because they’re protectors, we should respect them – even if we don’t always listen to them. They deserve to be recognized.

Is a fear of heights rational? From an evolutionary perspective, yes. The risk of falling was largely unpredictable and represented a threat. Is it rational in a skyscraper? Probably not – but by acknowledging the roots, we can understand how it makes sense even if the current conditions don’t match the need for fear.

One of Rogers’ key beliefs was that public television had the power to educate children (and adults) that feelings are mentionable and therefore manageable. He believed that feelings matter.

Mendable

A broken arm is mendable. The trauma of almost – but not actually – losing a sibling or child is mendable. We will, given time and the right support, grow past the traumas and perhaps even into stronger versions of ourselves. (See Posttraumatic Growth for more.) However, there are some situations which aren’t mendable. False accusations create a sense of doubt and fear around a person which aren’t fair – and they’re non-repairable. Cardinal Bernardin was falsely accused of sexual abuse of a college student, Steven Cook. While the accusations were ultimately proven false, they left a permanent mark on a good man. Still, the Cardinal proved what Dr. Orr, one of Rogers’ mentors, had said long ago about the only thing that evil could not stand – forgiveness. Bernardin forgave Steven Cook and showed that even broken hearts can be mended.

Perhaps if we need to know that we’re mendable and that we can be mended, we can find assurance in The Simple Faith of Mister Rogers.