If someone would ask you how big you wanted your team to be, your default answer might be that you want it to be big. After all, the larger the team, the more you can get done. However, the default answer may not be the right answer. There are a set of factors that work against large groups getting anything done. So, when you’re planning your teams for Microsoft Teams, how large should they be? There isn’t a one-size-fits-all answer to the question. Instead, the answer comes at the balance of having to move between teams and being able to focus on the work that you’re responsible for helping with.

To make our examples concrete, we’ll consider how many teams to create for individual departments, though the same logic can be applied to any large-scale group of people.

Groups of Groups

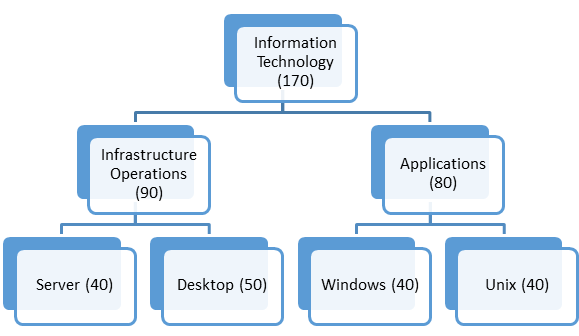

Before getting to the framework, it’s important to illuminate the fact that, in every organization, there are groups of groups. For instance, in information technology, there are typically operations or infrastructure groups and development or applications groups. Depending on the size of the organization, there may be groups inside of applications for the various applications that the organization utilizes. The infrastructure/operations group may be split between server and desktop operations or perhaps based on Windows versus Unix. A simple hierarchy for Information Technology might look like:

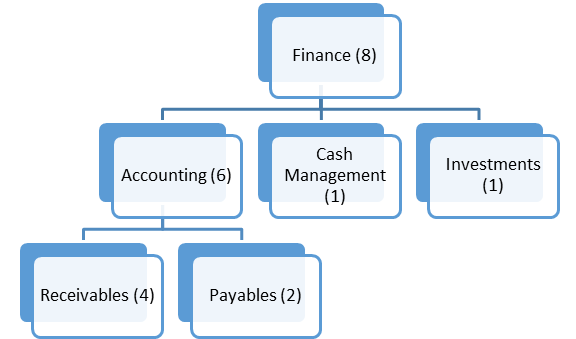

Information technology isn’t unique in that it consists of groups inside of groups. Every organization is like this. Consider this hypothetical finance department:

The question becomes this: what level of the organization should be a team? Before answering that question, we must recognize the problems that partitioning seeks to solve.

Partitioning Problems

As with the default answer about how big the team should be, one option is to put everyone in one big team. The benefit is, of course, that there’s only one place to go. However, there are challenges. For instance, it’s hard to coordinate across multiple people to organize information. You either end up with a set of folders that is inconsistent, no folders at all, or multiple folders for the same thing. Finding what you need becomes almost impossible.

It’s also difficult to manage communications when there are so many people in one place. Consider a crowded conference room with hundreds of people each carrying on their own conversations. If you’re not in a conversation specifically, it’s going to be difficult to listen to the other conversations going on around you, because there’s so much noise. Team conversations have the same challenge. When there are too many people, the conversations become too much to keep up with – or even pretend to keep up with.

Microsoft Teams channels help to mitigate this by partitioning conversations into separate, smaller spaces. This is akin to breaking up the one large conference room into multiple smaller conference rooms. This is a solid strategy for dealing with the noise but is difficult to execute in the moment. Once a large group has gathered, getting them to move into separate rooms is hard.

In general, we partition things into separate spaces to make them more manageable. In organizations, we partition folks into groups of people that can be managed. We put up shelves in closets to help us organize the things we put there. Within the partition, it makes finding and managing items easier – but with the added challenge of figuring out which partition we put things in.

Where Did I Put It?

Most of us have had the experience of walking around our house trying to find something that we put down. The problem is often that there’s no one set place for whatever we’re trying to find. Because of all the possible places that we could put it, we’re not clear which one we happened to choose. We still have the same findability/discoverability problem, but this time, instead of inside a space, it’s between the spaces that we might have chosen.

We have the same problem when we create too many smaller teams and channels. The number of options becomes more overwhelming as the number of options inside the space makes finding your way around inside the space more manageable.

Striking the Balance

With challenges and benefits on creating one large space and putting everyone in it, and the converse idea of creating a team for every one or two people, the trick is to strike the balance between too few and too many groups. A starting point for this balance is working from the perspective of how many people can effectively be in a team.

Stable Social Relationships

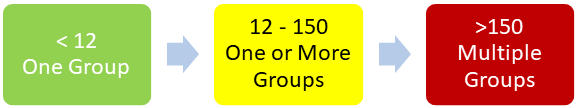

The research done by Robin Dunbar seems to indicate that humans are capable of roughly 100 to 250 stable social relationships. A number around 150 people shows up in many different naturally-occurring groups across history. This leads to the conclusion that groups should be no larger than about 150 people.

On the other hand, there’s research on optimal team size, the effect of team size on innovation, and the change in conversation as the number of participants change that suggests that, below about five people, conversations don’t demonstrate the kinds of characteristics that are ideal. Several of the research models cluster around the idea that, with about eight to twelve people, conversations start to break down and become less effective.

This leads to some general guidance that fewer than 12 people should be one group, and more than 150 should be multiple groups, as shown in this diagram:

Multiple Teams

If we apply these guidelines to the organizational charts provided above, the Information Technology department might have teams of:

- Information Technology

- Infrastructure Operations

- Server

- Desktop

- Applications

- Windows

- Unix

An employee doing Unix application support would be a member of Information Technology, Applications, and Unix, indicating their part of each of these groups. In practice, the department may find that there’s not much communication at the Information Technology level or at the level of Infrastructure Operations and Applications. As a result, it may be advisable to remove the Infrastructure Operations and Applications teams and use the Information Technology team with Infrastructure Operations and Applications channels. That decision would be made based on the degree to which there’s important information to be discussed in each of the teams and how much noise or unwanted information will be there.

The Signal and the Noise

In any given day, we’re bombarded with useless information, from SPAM email that we have no interest in to advertisements for injury attorneys looking for clients. This useless information is called “noise.” It’s the stuff we don’t want. The things that we do want to reach our consciousness is the “signal.” The signal includes the important information that we can learn from or act on. However, the signal is too frequently obscured in the noise. As we’re deciding where to partition groups of people into separate teams and channels, we’re trying to make it easier to get rid of the noise without making it harder to hear the signal.

In email discussion groups, you will find that some groups have only a handful of messages per month and others have hundreds of messages every day. With a few messages, it’s easy to review every message to see if it’s important. If only one message per month is relevant and valuable, the signal to noise ratio is pretty good. In discussion threads with hundreds of messages, it will take many messages being relevant to keep the same signal to noise ratio.

Creating channels in teams allows for conversations to happen inside the team but without everyone in the team needing to be a direct part of those conversations. These side conversations are good, because they lower the amount of noise that everyone else needs to cope with.

Sometimes larger teams can create channels to subdivide the conversations in ways that make them relevant and interesting.

Part of Many

In the above scenario, it becomes necessary for a single person to become a part of multiple teams just to maintain the right connections inside of the Information Technology department. Two or three teams for your department isn’t bad at all – however, as the department size increases, it becomes necessary to have more levels of division and therefore more teams that each person is a member of.

More importantly, as teams are created for non-departmental needs like cross-departmental projects, committees, centers of excellence, and interest groups, the number of teams that one person may be a member of multiplies. This creates a challenge to decide where the right place is to connect with colleagues and to keep up on the relevant conversations. This may lead to fatigue and, ultimately, the response that the only conversations that are relevant are the ones in which you’re directly mentioned. These are highlighted in the activity function of teams across all the teams you’re a part of, so it becomes possible to focus your attention only on those things where people are waiting on answers from you when it’s necessary.

Choice anxiety increases the more choices that a human is given. The stress of making a choice between seven teams may be manageable, but the stress of deciding between seventy teams may not be. The result is frequently that nothing happens because of the anxiety of choosing where to post the comment or file the document.

Pattern Matching

Making decisions one at a time for each department will only get you so far. Another approach is to consider what most teams are going to look like. If most departments are going to exist in a single team, then even a larger department may stay in one team – at least initially for consistency. This pattern matching makes it easier for users to rationalize the way that they’re expected to behave.

Therefore, when an answer doesn’t readily present itself for a single department or group, it’s sometimes helpful to consider other peer groups to see if one of those groups is easy to assess the right answer – and then copy that answer and apply it to other departments or groups.

Conclusion

There’s a lot of room between 12 and 150 people for decision-making about whether to have one or multiple groups; however, in practice, numbers close to either edge tend to be relatively obvious. If you’ve got 120 people that behave as one cohesive group, then one team may make sense. In most cases, groups of that size operate differently.

Leveraging these factors, you can identify the cases where you clearly need more than one team and where you clearly only need one team. In those cases where there is still no clear answer, either one or multiple groups will be – relatively speaking – equally fine.

No comment yet, add your voice below!