Conflict: The Value of Time

When in the middle of a conflict, it’s too easy to get swept up in the rising tide of emotions and believe that the conflict must be resolved immediately. Our brains are evolutionarily wired to focus on the biggest threat, and a conflict is a threat. While it may not be a physical threat to us, the threat to our ego that we might be wrong is still very real. Our body’s response to a threat is a cocktail of chemicals that can make it hard to think.

Physiological Impact

If you perceive danger, in an instant, your body is going to release a set of hormones into your bloodstream to prepare it to respond – immediately. This so-called “fight or flight” response has been known for ages and the lead chemical in this cocktail is adrenaline. It’s a part of a set of signals to shut down the long-term processes – and thinking – and make all energy reserves available for addressing the current threat. (If you want to know more about the physiology of the threat or stress response, see Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers.)

Our immune system shuts down, as does our digestive system, but that’s not the most disturbing and challenging aspect. What happens is we narrow our focus and stop looking for alternatives and solutions. (For more, see the book Drive.) In short, our body’s own approach to the stress of an eminent threat to survival creates challenges when the threats we’re facing are more psychic than physical.

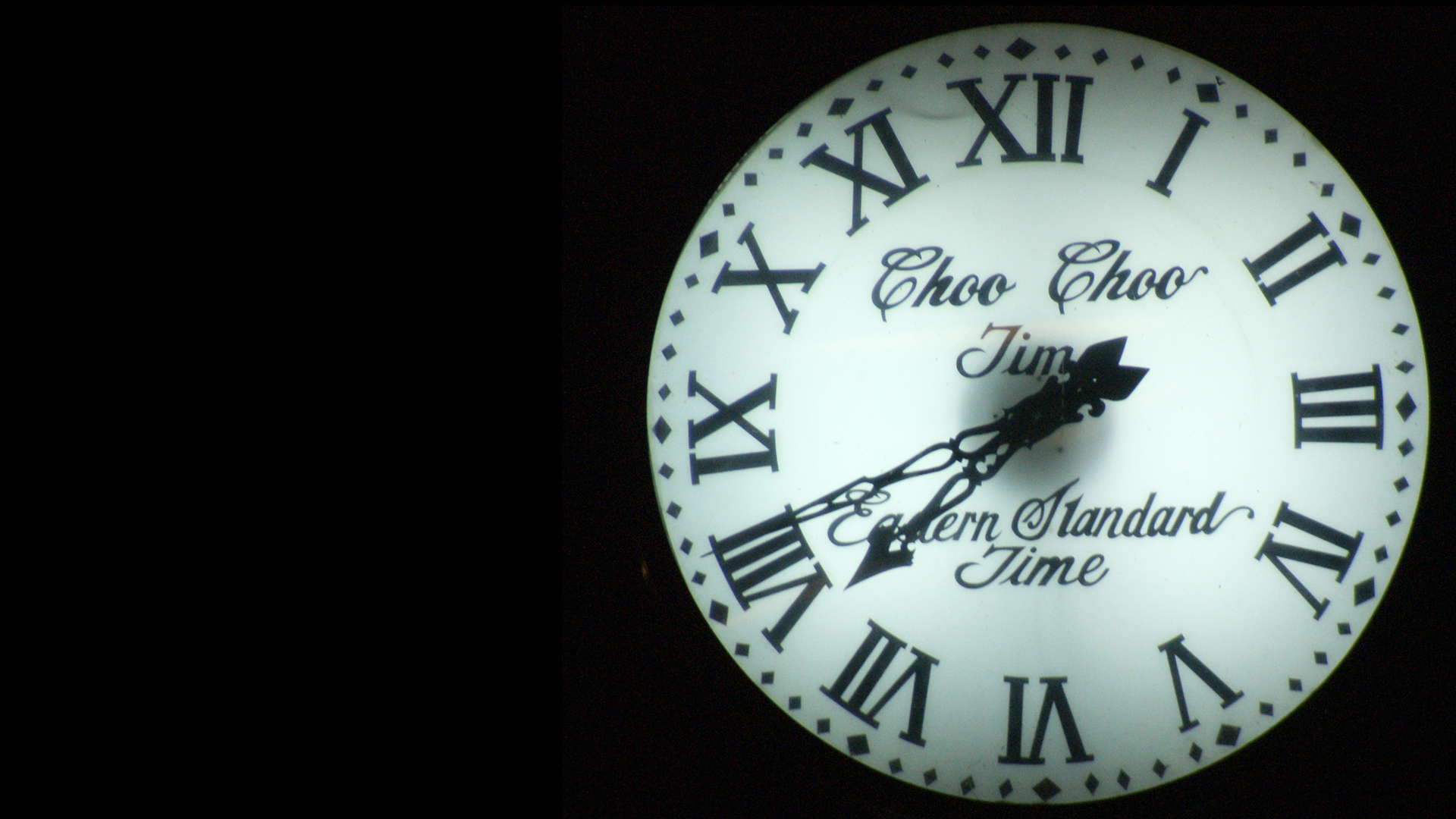

While there are many chemicals released when we’re facing danger, adrenaline is the key actor in our inability to consider alternatives, and it has a half-life of about 20 minutes. That means creating space and time in a conflict may be just what the doctor ordered.

The Science of Relationships

John Gottman is famous for his ability to predict with 93% accuracy the ability for a couple to stay together after just three minutes. It’s three minutes of fighting, but with that, he can tell signs of whether they’ll make it or not. (See The Science of Trust for more.) One of his recommendations for improving the odds is to slow things down and more rationally consider the situation. This advice helps in part because of the decay of the adrenaline but also because it allows you to focus on what’s important.

One important point about the additional time and space to be created during or after a conflict is to not rehearse the conflict in your mind. Our brains are incapable of determining whether the threat is real and now or whether it’s something old and imaginary. This is why, while watching an action film or a horror movie, our pulse can jump sky high – our brains can’t make the distinction between where we are and what’s on the screen.

Let It Breathe

The advice, should we find ourselves feeling physically or ideologically threatened is to wait for the chemicals to dissipate. However, the advice is equally good when facing conflicts that seem less immediate and for which the reasoning is complex. Sometimes, a conflict isn’t really a conflict at all. It’s an artifact that the other person hasn’t had a chance to think about all the information provided to them to come around to our way of thinking.

As a result, sometimes the best thing to do to get a new idea supported is to allow the powers that be an opportunity to consider the proposal and decide that our approach is better than the old existing ways of doing things.

Either way, slowing a conflict down is good advice for any stage of disagreement.