While speaking with a friend recently she said that she had written in her notebook a concept similar to Snapchat that she had never followed up on. I once knew someone who said that her father had invented the technology behind invisible fencing but never did anything with it. Seeing David in the Stone is about finding and seizing great opportunities. In today’s world we’ve seen millionaires rise out of simple ideas executed well. Whether it’s Facebook, YouTube, or one of the other dozens of companies that have sold for impressive amounts of money, it’s clear that opportunities are around us, it’s just a matter of us finding and seizing them.

About Joe

Seeing David in the Stone isn’t exactly mainstream reading (not that most of what I read is mainstream reading). It was published in 2007 and hasn’t been picked up on a New York Times best seller list so how did I find it? Well, as it turns out the book is written by James Swartz and Joseph (Joe) Swartz with contributions from the rest of the family. Joe is someone that my wife Terri had met and so we started up a conversation. Out of that conversation he gave me a printed copy of the book to read. As I’ve mentioned in my Research in the age of electrons post, I’ve mostly migrated to reading books on Kindle – however, I decided to make an exception for this book, because in our conversations Joe was sharing different perspectives on some of the same folks that I was quoting in my works. I wanted to see how his perspectives differed and how I might get some new insights.

One of the interesting things about the approach of the book is that it’s narrative based. That is, that it’s told in the style of a story. As you may remember from my book review of John Kotter’s book Buy-In, I’m not a big fan of narrative based books. However, as Joe pointed out during our conversations, that’s pretty normal as men often are “get to the facts” people and women are much more story focused. We’ve learned for thousands of years through story telling so it’s certainly aligned with how we learn.

Talent and Hard Work

In Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers he spoke of how 10,000 hours of purposeful practice often made folks great. Seeing David in the Stone quotes Michelangelo with “If anyone knew how hard and how long I have worked to become what I am today, they would no longer think such great things about me.” It’s a quote I hadn’t seen before and one that I appreciate. I’ve heard it other places too. James MacDonald mentioned in a series “Lord, Change My Attitude” that people want his success – as an author, speaker, and pastor – but they didn’t want the hard work it took to get it. He spoke of long drives to small churches with little compensation (my calculations made it enough for gasoline and a sandwich.) It seems like many – but perhaps not all – of the people that we see as successful have spent years and years of hard work to elevate their practice.

Seeing David in the Stone walks through the dichotomy of the idea that in order to become truly good you have to practice and to practice you have to have some initial skill to build on. However, as Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi explains in Finding Flow – getting to that higher state of functioning which he calls flow, requires the right balance of skill and challenge. You can start with relatively little skill if the level of challenge is relatively small. The state of flow fuels the process of learning and becoming more interested in the practice.

The point made clear in Seeing David in the Stone was that the innovators – the people like Edison who transformed industries – often had become experts not only in the area that they were seeking to innovate in but in complementary categories as well. For instance, Edison was focused on making safe electric lighting. In order to understand how to create this he wasn’t focused just on the properties of electricity. He focused on how lighting was done and hired the skills necessary to create a light bulb. He found glass blowers, metallurgists, and chemists. He wanted to know as much as possible about the way things were done today – and was willing to engage experts in other disciplines to get the additional experience he needed.

Becoming an expert in any topic is in and of itself hard work. It is countless hours of practice, listening, and experimentation. However, hiring experts to come along side of you is a different kind of hard work as well. It’s hard to get OK with the awareness that you won’t know everything – you’re accepting that you need others no matter how knowledgeable you are.

Long Term and Short Term

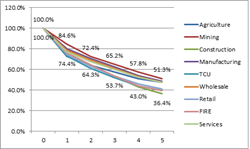

As a consultant, I’m intimately familiar with short term focus. As a consultant you’re billing and will eventually create an invoice and, mostly, get paid. Working as a consultant I’m working on the short term. I’m working on the money that I’ll have soon. This works really well – right up to the point where it doesn’t. Anyone who has been in business for themselves will tell you that if you stay too focused on the short term billing and fail to look at the long term of who the next client will be – and on sales – you’ll eventually be in trouble. In fact, as the chart below shows, the 3 year survival rate for businesses are in the neighborhood of 60% — meaning 40% of the businesses have failed.

Five Year Survival Rates for Small Businesses (Credit: http://smallbiztrends.com/2012/09/failure-rates-by-sector-the-real-numbers.html)

The threat for survival if you’re focused just on your short term needs is very real. If you’re always living in the short term – moment to moment or paycheck to paycheck – there will be an event that will throw you out of whack and you’ll have a problem. While we can’t attribute all of the failures to a lack of long term awareness, there’s no doubt that some businesses never escape the trap of the short term. I blogged about this in “SharePoint Isn’t Your Biggest Problem – Right Now.” If you want to see success in the long term you can look to the Jesuits. They are a 450 year organization whose purpose has a very long term focus. (See Heroic Leadership)

Seeing David in the Stone quotes Bill Gates as saying “My success in business has largely been the result of my ability to focus on long-term goals and ignore the short-term distractions.” Ultimately it’s a balance between the necessities of the day and the aspirations of tomorrow that create long term and sustainable growth but the balance between the needs of the present and the preparation for the future is delicate. It takes skill to get both to fit in the space we have for our lives.

Lifelong Learning

Kotter in Leading Change talks about how lifelong learning is essential to good leadership because lifelong learners take more risks than do the rest of us. Mindset sets us straight on the fact that we can learn, grow, and change throughout our lives. While not using the words lifelong learning, Seeing David in the Stone conveys that life is about learning and that everyone who wants to be a successful leader must continue to strive to be better. In fact, step 2 calls for individuals to use powerful learning processes – that is to say that everyone should be intentional about their learning. How do you continue to grow – even when you’re at the top of your game?

Maybe the answer is in the idea of developing multiple mastery.

Multiple Mastery

I often joke with folks that I don’t know what I want to be when I grow up. I say that because I started my career as a software developer. I transitioned to doing networking – because it was challenging. When it became less challenging I shifted back to being a software developer. I started working on the Shepherd’s Guide because my clients were asking for help materials for SharePoint after I built a solution for them. That’s lead me on a journey to learn more about organizational change and what it takes to help organizations leverage SharePoint more effectively. In fact, I’ve written a book about it – Making Organizational Change Work from the Inside Out. I wouldn’t say that I’ve mastered everything that I’ve tried – things like Comedy are still on my backlog of things to get better at. (See I am Comedian.) However, I do recognize the need to

In 2004 I wrote an article for Internet.com titled “Renaissance Man” where I spoke about how we pick up knowledge and skills that are useful to us. I also discussed the idea in an article titled “Software Developers-Learn another Language” from 2003 where I was making a softer statement about the need to learn enough to be conversant in other areas. Ultimately the true breakthroughs in innovation rarely come from folks that know only one thing. The folks who do truly remarkable works are people who have multiple areas of mastery. Extraordinary Minds is four profiles including Mozart who was, obviously a master of his domain; music. So there are exceptions. However, Leonardo Di Vinci was even more highly regarded for his ability to be a master of multiple domains.

Whole and Parts

One of the most powerful aspects of Di Vinci was that he was capable of seeing the whole. He leveraged his existing skills into the new domain every time leveraging his awareness of how things were connected and fit together. He created designs which were focused on how the whole worked together. He was, in some senses, the original systems thinker. (See Thinking in Systems and The Fifth Discipline.)

One of the challenges we have with our fragmented, piece it together culture of today is that we often end up focused on our narrow vision and fail to see the broader implications. This sometimes leads to a Tragedy of Commons (where rational individual actions drive dire consequences for the whole.) Stories abound of managers who are looking out for their department at the expense of the larger organization. We optimize our individual pieces without taking a step back to make sure that all of the pieces work together correctly, are appropriate, and are even necessary.

Leaders are able to optimize the overall system and then refine the behavior of the individual components of the system – doing it the way that makes the most sense.

Seeing David in the Stone

Ultimately, the key to innovation is being able to see what is hidden and to bring it to the surface – to see the David in the stone. It’s not quite enough to see David in the stone – you’ve also got to have the tools to free David from that stone. Along the way Michelangelo had to see David in the moments before his fight with Goliath. He also had to develop his skills to the point where he could free David from the stone. For us this means the development skills, and the insight that comes with experience. (The kind of insight that Gary Klein discussed in Sources of Power.) So build your skills and then go find your David in the Stone.

1 Comment

This piece was cogent, wet-wlrilten, and pithy.