Book Revisited: Theory U

This post is a bit odd in that it’s not a book review – but it’s about a book and more broadly about a theory. This post is about Otto Scharmer’s Theory U. The book Theory U expresses the ideas from a personal context, and Otto’s subsequent book Leading from the Emerging Future expresses the same ideas from group, cultural and societal perspectives. Recently, I was given a chance to revisit my thinking on this material – and very shortly after that finished a book with strong correlation by another author. (That review is forthcoming.) This pressed upon me the importance of Otto’s work – and the need to make it more accessible. In this post, I endeavor to pull together the other places where echoes of Theory U can be found and attempt to weave together a concrete story about how people can grow through a process that looks like Theory U.

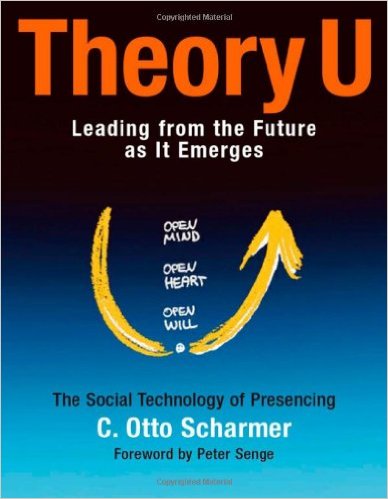

Seven Inflection Points of Theory U

My objective is to talk about the seven inflection points of Theory U, and more importantly how to move from one inflection point to another. The seven inflection points are:

- Downloading – Reacting to patterns of the past and viewing the world from inside your mind.

- Seeing – Suspending judgement and accepting that our perception of reality isn’t the only one.

- Sensing – Seeing from the perspective of the system that we’re all a part of.

- Presencing – Transitioning our thinking from the present to the future.

- Crystalizing – Experimenting with our mental model and investigating possible futures. Identifying paths forward that are the “best.”

- Prototyping – Developing small-scale tests that validate whether our mental models are right.

- Performing – Implementing the changes we prototyped in to the larger systems of our lives and our world.

I’ll explore each of these in the following sections and talk about how to move from one inflection point to the next.

Downloading

At this inflection point, we’re not really paying attention. Like the number of stop lights we passed while coming into the office the last time, we’re just not focused and engaged. We stop our car at stop lights automatically. We don’t have to pay attention – so we don’t. We use our patterns and our history so that we don’t have to engage our brains.

Engagement, or attention, is processed in a part of our brains called the reticular activating system. In addition to attention, it regulates our sleep-wake cycle. It’s the gas pedal that decides how much energy to use at any given time. The more engaged our reticular activating system is, the more engaged we are. It responds to conscious control at times, but also responds to pattern recognition. That’s why when you buy a new car, you suddenly recognize all the other people on the road who have the same car as you. The reticular activating system sees the pattern and pays more attention. (You can find out more about the reticular activating system in Change or Die.)

When the reticular activating system is in full power mode, we switch from a lizard-like, automatic stimulus-response processing into a more thoughtful, primate-like rational thinking. When we do this, we have the capacity to transcend our previous patterns and move towards making conscious decisions about how we see the world and how we listen. (See Thinking, Fast and Slow for a detailed conversation about these different systems of thinking.) While research indicates that our brains have a power consumption cap, it’s a high-cap. They vary, but estimates of the brain’s power consumption generally fall into the range of 20-30% of our body’s entire energy processing. Contrast that with the roughly 2% of our body mass, and you can see why having a regulator for our energy consumption is an important tool. (You can find more about our brains having a fixed capacity for energy (glucose) processing in The Rise of Superman, and more about glucose problems in the brain in The End of Memory.)

We spend most of our time with the reticular activating system in the off position. Expressed in the language of Jonathan Haidt in The Happiness Hypothesis and Dan and Chip Heath from Switch, we have a small, rational rider sitting on the back of a big, emotional elephant wandering down the default path. That is, we believe our rational selves oversee our walk, but more often the elephant is the one walking – and she’s taking the easy path.

If we want to move from downloading to seeing, we need to press down on the gas and pay attention – so we can move to rational thought about what we’re doing. We must wake our rider and have them steer our elephant to more productive paths.

Seeing

In our lizard brains, there’s no room for anyone else’s perspective. It’s simple pattern-matching. If we’ve seen the pattern before, then we’ll expect the same outcomes. This is particularly true if we felt fear when we saw that pattern before. (See Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers for more on what happens in our brains when we are stressed.) However, how we perceive reality isn’t reality. It’s a trick that our brain plays on us. It makes up any missing data and doesn’t let us know it’s doing it. David Eagleman in Incognito artfully explains many ways that our brains lie to us and keep us from realizing the holes in our processing.

Another scholar, Chris Argyris (whose book, Organizational Traps, is very good), applies a ladder to why we have different perspectives. In my review of Choice Theory, I mentioned Argyris’ ladder of interference and how we see the same data and experiences, from which we select the data that is important to us (thanks to our reticular activating system), we apply meaning to that data, then we make assumptions, draw conclusions, develop beliefs, and finally take actions. Since everything except for the first rung of the ladder is internally generated, it’s quite easy for two people can view the same incident differently. The easiest way to see this is to watch the commentary after a political debate. Amazingly, both sides will have both won and lost – if you listen to all the perspectives.

That’s at the heart of seeing, which is listening to all the perspectives and keeping space to pay attention to another person, and accept and appreciate that their perspective is different than yours and there’s some amount of truth to it. (See How to Be an Adult in Relationships for more on attention, acceptance, and appreciation – as well as affection and allowing.)

What moves you from seeing to sensing is an appreciation for the fact that we’re all related and that everything in life is a system of relationships – not just individual objects on which the laws of cause and effect apply.

Sensing

When Gary Klein started researching fire captains, as he describes in Sources of Power, he was trying to capture their essential insight into the inner workings of fires and how they could direct firefighters. Much to his dismay, the fire captains resisted his assertion that they followed a rational decision-making process. They further frustrated him with an inability to explain what they were seeing, until he realized that they had developed a mental model of how fires worked and quickly simulated how the fires were operating and what they could do to change the outcomes. They had discovered the internal systems that drove the fires.

A more systematic approach to systems is decomposing the system into its component parts and understanding the relationships. This substantially more explicit approach is well covered in Thinking in Systems. It presents a detailed view of how the different stocks and flows influence systems. With an understanding of these components, it’s possible to simulate what might happen in the system the same way that fire captains could simulate what a fire would do.

Whether you’re walking down the implicit – sometimes called “tacit” – approach to understanding the world you’re in and how it reacts to an explicit approach, both lead to the same result. That is the ability to see changes in a system in a way that results in a positive desired outcome. (See The New Edge in Knowledge for more on tacit vs. explicit knowledge.)

Two words of caution are appropriate for systems thinking. First, Everett Rogers explains in Diffusion of Innovations that you can’t always predict the outcomes that you’ll get. Sometimes, introducing steel axe heads can degenerate an entire culture. Second, Horst Rittel describes “wicked” problems that are difficult to solve. Among other attributes, a wicked problem is one where the very actions you take to solve the problem change it. This means that the actual actions you take based on your awareness of the challenge makes it change – often in unpredictable ways. (See Dialogue Mapping for more on wicked problems.)

You move into presencing when you’re ready to use the mental model you’ve built to test ways to make your life – and your world – better. (Even if it means that you might not have accounted for all the things that you don’t know – like The Black Swan – that may come along.)

Presencing

Presencing is about listening to the world around you, disconnecting from your ego and will, and just being present. Buddhists believe that inappropriate attachment is a bad thing. Detachment is a virtue to be struggled for. (The Dalai Lama’s book My Spiritual Journey is a good way to learn more about Buddhist detachment.) Christians speak of pride, lust, and greed – basically valuing ourselves more highly than we should or than we value others. Christians are implored to become less connected to their ego. Paul’s writings in the New Testament about strength through Christ and stories like the good Samaritan lead to this separation of ego from the person’s behaviors. (Robert Greenleaf’s Servant Leadership is a difficult but worthy read about being a servant through becoming selfless.)

From a mystical point of view, it’s connecting to “the source.” Fundamentally, this is about shutting down the right parietal lobe of our brains. This is the portion of our brain that draws the line between us and not-us. When this portion of the brain is shut off during flow or intense meditation, we literally feel like we’re at one with the universe. In this state, we’ve no separate ego from the ego of the universe and therefore it can’t impede our view of the world around us. (See Stealing Fire for more about neurology and how our brains get to altered states of consciousness.)

With the perspective of oneness, we can move towards problem solving, and moving ourselves and our society forward. We move toward crystalizing plans of action.

Crystalizing

Every inflection point up to this point has been about the present. Each has been about our experience in the here and now. With crystalizing, we being to move towards shaping and creating our future. Instead of being aware of the gaps in our perception of reality and developing models to help us understand the current reality, we begin to push forward into the future. This starts by moving our models into the future and seeing what results those models generate. (The Time Paradox talks about individuals’ predisposition to see things in terms of the past, present, or future, so it may be that taking this step is difficult if you have a past or present focus.)

As we begin to crystalize our thoughts on outcomes we could expect with relatively small changes in input, we need to develop the skills to socialize those thoughts. We don’t need to create buy-in as much as we need to test our understandings to see what others believe. (The book Buy-In is a useful tool for generating buy-in when you’re ready to move past exploration.)

Tools like active listening (see Gordon’s Parent Effectiveness Training

for more on active listening) and techniques like motivational interviewing are good ways to begin to create the open and safe conversations necessary to effectively dialogue about potential futures. The book Motivational Interviewing is a good way to learn more about motivational interviewing. Ultimately William Isaacs wrote Dialogue to help us get into the state of dialogue with others that is essential to refining and socializing our ideas.

Moving from talk to action takes us to the next inflection point, where we prototype our proposed solution so we can test it.

Prototyping

In software development and Internet software as a service, there’s an “MVP”. The MVP is the minimum viable product. It’s what the organization needs to do to be minimally acceptable to the market – at least what they believe is minimally necessary for the market to adopt the product. This same concept applies to every idea we have for ourselves and our worlds. (See Launch! for more on the MVP.)

I love MythBusters – the Discovery channel show – where, invariably, they blow something up. My appreciation for the show isn’t exclusively the explosions. What I love is the process where they create a small-scale prototype and then scale up from there to their final experiment. What this does is allows them to learn and bring more knowledge to the end solution. When they’ve failed to prototype well, they’ve failed their experiments rather spectacularly. Prototyping, and accepting failure as a method of learning, is critical to anything we want to do in our lives.

Good prototypes even seek out failure modes. We create them with the idea that we’re looking to see what could fail, or how we could test our assumptions such that the failure teaches us something. With prototypes, we’re looking for high rates of failure and a high velocity of tests. (See The Righteous Mind for how we fail to test our assumptions for failure.)

Once our prototypes are done, once we know what will – and what won’t – work, we’re in the position to finally start performing.

Performing

Once we know what to do, it’s time to systematize the process of production. Gerber, in The E-Myth Revisited, talks about the need for systems and for the owner of an organization to make everything repeatable. Franchisors are successful because of their ability to create a system that anyone can follow for results, and that’s how we can perform in our life. That is not to say that we need to have an operations manual for our life, but rather we should instill the practices which work for us in a repeatable way. For instance, I’m reading and reviewing a book each week. That – for me – works to re-center, to think deeply, and to rejuvenate my soul. It’s a part of my weekly routine. It’s not rigid, but it’s a flexible framework that I use.

Performing for each person, and each organization, will be different. It’s important that performing provide you with the energy you need to find the next area of your life to get deeper into and to grow.

In Summary

I recognize that no quick article can do justice to a process as rich as Theory U; however, it’s my hope that this post provides a framework for thinking about Theory U that’s practical.