Robert Bogue

March 6, 2023

No Comments

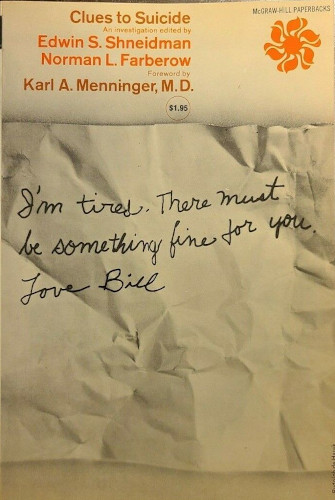

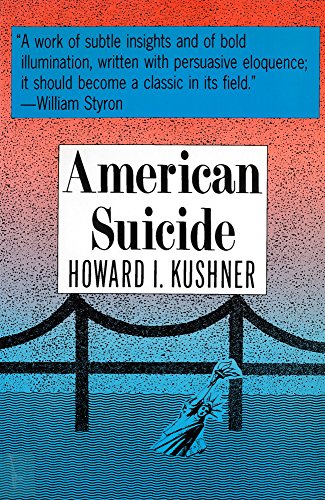

Every country seems to have its own unique quirks as it relates to suicide. Some have higher rates and some lower, but more than that, each culture views suicide just a bit differently. American Suicide: A Psychocultural Exploration (originally printed under the title, Self-Destruction in the Promised Land: A Psychocultural Biology of American Suicide) walks through the changing American beliefs about suicide and how they related to other beliefs across time.

It’s Not New News

At some level, we might believe that suicide didn’t exist, or it didn’t exist in the distant past at the same levels it does today. Because our records aren’t incredibly accurate past the last 100 to 150 years, there’s very little way of knowing the actual prevalence of suicide in society – nor its drivers. While there are historic studies of suicide, getting to accurate numbers is hard. There were very real criminal, shame-based, and financial reasons to hide suicide. Many suicides were likely categorized as accidents. In fairness, suicide numbers are hard to get today as well, as stigma still surrounds the death certificate that says “suicide.”

However, perspectives were a bit warped as well. For instance, the 1845 American Journal of Insanity warned against the dangers of “protracted religious meetings, especially of those held in the evening and night.” It seems that they may have viewed any degree of passion or rapture as a mental illness – or insanity. They believed that those who had mental illness needed to be controlled like beasts. Perhaps it’s no wonder that we evolved from this thinking to warehousing those who were struggling in state-run institutions.

Our Immortal Soul

Earlier thinking was that, somehow, the way we interacted with others, our behaviors, and our thoughts related to our immortal soul. That left little room for biological challenges to influence our behavior. In short, if you were behaving poorly, it was your fault. It wasn’t that you were struggling, healing, or hurting, it was believed that you had some sort of character defect.

It’s not exactly unheard of, as people used to shun those who had cancer because of the belief that somehow the person must have brought it upon themselves. It’s a natural progression. When things are mysterious, we assign mysterious causes. We believe the Devil did it when we can’t point to the process that caused it.

As we improved our diagnoses and treatments for cancer, it became both less of a death sentence and less of an indictment about someone’s poor character. We acknowledged it as a tragic reality of modern life. Similarly, we had discomfort around HIV and AIDS until it became treatable as a chronic condition instead of something unknown and untreatable.

Reticular Activating System and What You See Is All There Is

Our reticular activating system (RAS) is responsible for our sleep-wake cycle as well as for what we pay attention to. It’s why when we buy a new car, we see many more of that type of car on the road than we ever did. It doesn’t mean that the car is more prevalent – it means that we’re suddenly paying attention. (See Change or Die for more on RAS.) Daniel Kahneman in Thinking, Fast and Slow spoke of a related tendency in humans, which is to believe that what we see is all there is. The more that we research a topic or the more it’s reported, the more prevalent it is. Anthro-Vision explains that murders aren’t more prevalent than they used to be. Rather, there’s simply better coverage of them in the media. This creates the perception that they’re more prevalent.

If you’re new to researching suicide, you may think that it’s a new thing. However, the more you look back into the past and the odd perspectives that people had – and the rituals that evolved around the bodies of those who died by suicide – the more you realize that this isn’t new at all. We can go back to the statistics of the 1800s, or we can look at the news stories that warned of epidemics of suicide – in the early 1900s.

There’s little argument that suicide statistics are increasing – and probably the rate is increasing. However, there are questions about the limitations of the statistics we have. With a history of criminalization and church condemnation, there’s little question that suicides were frequently under reported. Is some of the climb in suicide rates that we’re seeing today the result of better statistics and greater reporting? We don’t know.

The idea comes from the work of Amy Edmondson and is recounted in The Fearless Organization. It’s the paradoxical finding that medication errors increased after psychological safety training that was designed to make it safer for people to report issues – and therefore be able to address the root causes. When the rates on the unit rose, it got everyone’s attention until they realized that the rates didn’t rise – the reported occurrences did. In the pre-safety culture, some events were simply not being reported.

Pathological Condition of the Brain

The first five editions of Medical Jurisprudence of Insanity (1838-1871) claimed that suicides were the result of “those who have been affected with some pathological condition of the brain.” This with the circular logic that only someone who was insane would attempt suicide has led to a persistent – and incorrect – belief that people who die by suicide have a mental illness. Frequently, this is quoted at 90%. The number ends in a zero, so we know it’s an estimate (since statistics are rarely so clean). However, it’s still widely cited as fact or research supported. (Complicating this are “research” articles that seem to back this up but have substantial methodological issues.)

Shneidman in The Suicidal Mind puts forth the idea that suicide is a solution to solve psychache – psychological pain. This makes sense in the broader context, because people in pain often behave in ways that are difficult to understand – and our brains make very little distinction between physical and psychological pain. (See The Neuroscience of Suicidal Behavior for more.)

Social Capital

Robert N. Reeves wrote in Popular Science Monthly (June 1897), “Where the population is dense and the law of health neglected, where dirt is common and vice flourishes, where the poor are concentrated, and where fortunes are made and lost in a day will always be found the highest rate of suicide.” Reeves has a point. The point is that in places where there is the least stability, there will be more opportunities for loss, and that loss can drive suicidal behaviors. Some of the aspects of this are obscured.

“Where population is dense” leads to a variety of situations that can lead to loss. Competition is greater with higher density – and that can itself lead to loss. More broadly, however, the social glue that causes more altruism in smaller settings begins to give under the intense strain of larger groups. We stay together for our own survival. If we can begin to release a few people, they’ll experience loss while the broader group may not.

If we want to reduce suicide, one aspect of this should certainly be the development of safety nets that catch people when they’re the most vulnerable and help them to make their way through difficult situations.

The Gap Between Statistics and the Individual

One of the challenges that exists in any sociological challenge is that the statistics that power identification of opportunities fall short of the capacity to predict outcomes on an individual basis. Research has demonstrated a correlation between alcoholism and suicide. A percentage of people who are alcoholics will die by suicide. We can say that the percentage is greater than in the general population. What no one can tell you is whether Bob or Suzi or Jim will die by suicide because they’re alcoholics. This represents a problem for suicide prevention.

We amass more research that explains the variations, and we still end up with screening and assessment tools that do little better than chance at correctly identifying those people who are going to die by suicide. That’s a problem.

Pathways

In Pathways to Suicide, Ron Maris attempts to lay out a set of transitions that the suicidal person goes through. Ideally, it’s a pathway from sane, mentally-healthy living to making the decision to take their own life. There are numerous problems with the approach, no matter how valiant the attempt. Not the least of which is the data that says that more than 50% of suicides are impulsive. That is, they weren’t considered more than a few hours before their act. (See Joiner’s Myths About Suicide for a discussion about this controversial idea.)

However, if the other group was on a suicidal path, then we’d expect to see that those who walk further down the path become progressively more likely to die by suicide. It’s not clear that this is the case. Of course, one can accumulate risky factors, but the degree of overlap between different factors and the direction of the causal arrows between them is such that it’s impossible to say with certainty that one person is – or isn’t – more or less likely to die by suicide. We simply don’t have the predictive capacity in any of our tools to say for sure.

In Extreme Productivity, Robert Pozen explains the random path that his life has taken – and he’s not alone. We can’t say that one path leads towards death by suicide, because even if we could, there’s no one path.

Statistical People

The problem that leads to the unpredictability of personal experiences is in an assumption that breaks down at the level of the individual. Statistics and the math behind it make a fundamental presumption that all of the data is the same. Statistical Process Control (SPC) was a boon to quality control inside of manufacturing. The idea is that you can predict when parts are going to start to go outside of tolerance and intervene when they do – or right before. If you have a machine that cuts widgets, and the machine has a tool that can dull over time, then you can predict when it will fail and thereby learn to replace it at precisely the right time.

This operates at the level of homogeneity. All the tools are the same, and all the parts are the same, therefore the failure is predictable. Individual differences will arise due to small fluctuations in the tool itself, but they will be sufficiently small as not to matter.

Humans, on the other hand, are immensely diverse. Two humans that appear the same may end up on radically different trajectories, as Judith Rich Harris beautifully explains in No Two Alike. Reiss explains these differences based on motivators in Who Am I?, but others have had other ways of identifying differences as well.

Because humans are fundamentally complex and not the same, the neat models of statistics break down. (See also How to Measure Anything for more about where statistics work and where they fail.)

The Expectation Gap

In Extinguish Burnout, Terri and I expose the challenge of expectation gaps. We share that burnout is those feelings of inefficacy we get when we have high expectations that we can never meet. We begin to feel hopeless that we’ll ever achieve them – rightly so – and in the end, we’ll end up in burnout. We see this same expectation gap in suicide as well. Suicide seems to separate into two different groups along the dimension of performance. I believe that it’s the averaging of these two different groups that sometimes leads to results that aren’t actionable. (See The Innovator’s DNA for an example of the problems of averaging when there are two different fundamentals in the data.)

Group 1 are those who have low performance drives. In this group, the conditions lead to a desire for suicide. There are endless reasons why people in this group are unfairly treated, and how the conditions that lead to their desire to die may be caused by events outside of their control.

Group 2 are the curiosities. When you look at their lives, they seem to have it all together. They have high expectations, and for the most part, they meet them. Consider celebrities in this category. They are, by definition, popular. They’re making money and enjoying a life that most people will never get a chance to fully experience, yet they want to die. What can explain their desire?

The answer may live in the gap between their expectations of their performance and their actual performance. They expected their album to be double-platinum, and it only became a platinum seller. With no expectations, this is amazing – but from the expectations, it’s a let down or a loss. It doesn’t have to be a celebrity. We’ve seen civic leaders and experts within their field die by suicide. Sometimes, it’s possible to track their expectation gap, and other times not so much.

What if you bought a house you could afford, went to a job you liked, had a primary relationship that was good, a new dog, and plenty of social connections? You were recognized for your contributions to others, thereby mitigating any concern that you’re a burden. (See Why People Die by Suicide.) In short, it looks like all is going well. Then, a small disturbance, like the death of a friend, creates ripples on the water of your life. What could explain your desire to die?

The loss creates an altered trajectory of your life. That person will no longer be a part of the future. This may cause you to take stock of your current situation. With high expectations, it might be that you’ll decide that you’ve not measured up to the standards you had for yourself.

Serotonin

There’s been a great deal of interest in serotonin in recent years. We’ve built chemicals to prevent its reuptake in the synaptic gap, and they’ve had some degree of success in helping people with depression. (See Warning: Psychiatry Can Be Hazardous to Your Mental Health for a countervailing view.) What we’ve learned about the neurotransmitter may explain why we like Thanksgiving so much.

Tryptophan – found in turkey – is a precursor to the development of serotonin, and it’s something that our bodies can’t naturally synthesize. Serotonin is manufactured in the brain, and therefore we need to get tryptophan from our digestive system through the blood into our brain. It turns out that the blood-brain barrier is a very competitive space, with many molecules trying to make the transition at the same time.

It also turns out that an increase in insulin – which is the natural response to a large number of calories eaten – makes it easier for the tryptophan we eat to make its way into the brain and to be used in the construction of more serotonin. It’s a complex, convoluted process, as biological systems often are. But it’s a pathway that can help us understand why we can feel so good after a big turkey dinner – even if we feel bad that we ate so much.

Depression and PTSD

Konrad Lorenz noticed an odd behavior in geese and ducks. They’ll search for a missing partner for days. It seems they can’t seem to make sense of the loss, and therefore they keep at it. This is not unlike depression, where our brain struggles to accept a truth that it cannot fathom. This is no different than the challenge of PTSD patients who are seeking to integrate a memory that they cannot accept. (See Transformed by Trauma for more.) In the end, it seems that depression and PTSD are both attempts to integrate information about a world that doesn’t match the way we see it internally – or the way we want to see it.

The story of American Suicide is one of change, depression, and trauma that is well worth the read.