Book Review-Trauma Therapy and Clinical Practice: Neuroscience, Gestalt, and the Body

Book Review-The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business

It’s five AM, and the alarm hasn’t gone off yet. I roll over gently, grab my iPad, and start reading. I’m not checking email or catching up on the latest news. I’m reading. It’s my habit, and this one, powerful habit has allowed me to read a book each week for years now. My wife is sleeping next to me, curled up in one arm as I use the other to hold, highlight, and flip pages in the Kindle app. (Which is a skill in and of itself.) This book is about The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. Most of what we do is a habit. It’s beyond the everyday wanderings of our conscious thoughts. Like the number of stoplights that were red when you drove to the grocery store, habits keep our cognitive load down and allow us to function in a world that’s overwhelming. (You’ve got a habit for driving and following traffic rules so few of us can recall the number of red lights we’ve seen.)

Keystone Habits

Duhigg starts by making it clear that we don’t have to change every one of these unconscious routines at one time. We don’t have to radically alter our entire lives in one moment to accomplish great things. In fact, greater success is found by intentionally swapping out just one habit at a time – ideally, the keystone habit.

Like the keystone set in architecture, it’s this habit that the other habits are built on. Changing this one thing starts a ripple effect that can change everything about our lives – assuming, of course, that we can find the keystone habit and alter it. Before we can find a habit, we must understand what habits are. For instance, a habit like smoking can be a keystone habit. Once you eliminate smoking, excessive drinking, lack of exercise, etc., may easily change to healthier options.

Defining Habits

Habits are automatic and unconscious; but what do they do and how do we go about changing them? Habits may be typically unconscious, but they’re malleable. (See Peak for more about how elite performers make habits and make them conscious at times.) We can bring them into our consciousness to see what we’re doing and, with careful inspection, what’s trigging us to start the habit in the first place.

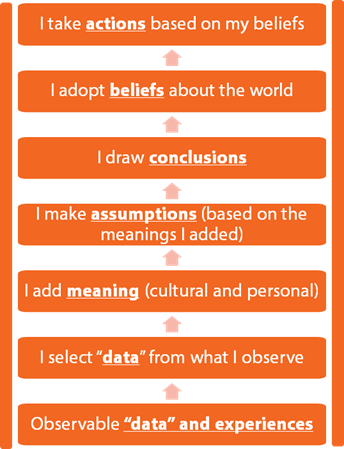

Habits have three basic components. First, there’s the cue. This trigger causes our brains to activate a routine – the next part of the habit. The habit ends in a reward of some sort. It could be getting to work, the sugar spike from that cookie you know you shouldn’t have, but you want, or something else entirely.

The key to changing habits isn’t in using our willpower to resist them. (See Willpower for more on willpower.) The key to changing habits is to find the right lever. Change or Die explains how, in most cases, folks who want to make serious life changes fall back to their old habits. Check the heart attack patient one year later, and you’re likely to find them back behind a plate of bacon and eggs instead of fruit and oatmeal. Substitution is the name of the game, and that is where marshmallows come in.

The Marshmallow Test

Walter Mischel’s simple test might be construed by his subjects as mental torture. Imagine the pains running through a child’s mind as they’re offered a tasty treat – like a marshmallow – or twice as much if they can wait a few minutes while the researcher is out of the room. For some, this was torture until they ate the treat in the center of the table. For others, they found ways of distracting themselves and allowed the time to pass by, so they could get twice the reward. (For more on this see The Marshmallow Test.) The interesting thing isn’t this torture of preschoolers but rather the techniques employed by those that were successful in waiting – or their success in life years after the simple test. Imagine higher SAT scores and better overall lives based on the ability to wait a few minutes for a marshmallow.

The real secret here is how to teach these young children – and adults – how to distract themselves, to change the focus of their attention, to something else. In doing this, it’s possible to flip the switch on the train tracks and route the habit train down another path – ideally, one that’s much healthier and more productive.

Interrupting the Cue

A cue is simple. It’s something that triggers your attention. It could be that twinge of pain you feel as you leave your vacation heading back to the real world. It can be the smell of chocolate cookies baking in the oven. It can be anything that your external senses can perceive – or any internal cue that your mind can conjure up.

The first choice for interrupting the cue is willpower. Willpower is an exhaustible resource, like a muscle that gets better with exercise – but with limited capacity. In some cases, simply identifying the cue that leads to the habit and being on the lookout is enough. A bit of attention from our reticular activating system (RAS) and a smidge of willpower and we can interrupt the automatic routing into the preexisting routine. (Change or Die has more on the RAS.)

One of the key challenges is that people don’t attempt to leverage their willpower to reroute the cue. Instead they try to suppress it – or they try to stop the routine once it’s already started. For most of us, this doesn’t work. Our willpower isn’t strong enough to suppress a cue. Our biology is wired to repeat messages that are ignored – often more loudly. The more you deny the cue exists, the louder and more insistent it will become, until it our willpower can’t hold it back any longer.

The other approach – to disrupt the routine once it’s started – is similarly ill-fated. Not only are you trying to use your consciousness to interfere with an automatic process, the delay in completion causes the initial cue to be repeated. A good model for thinking about this comes from Johnathan Haidt in The Happiness Hypothesis. The Elephant-Rider-Path model is my favorite mental model of how our mind works – and it says that the elephant (emotions and automatic processing) are in control, not our rational riders. The work of Kahneman in Thinking, Fast and Slow also explains this epic battle of the mind and how challenging it can be to win with our rational thought – since our unconscious mind can lie to us. (See Incognito for more on interesting ways that it lies.)

In other cases, where there’s too much to overcome, another strategy may be required. That’s the strategy of predecision. That is, before something occurs, we decide how we’re going to handle it. In effect, we rewrite the circuitry that routes from the cue to the routine. We can either force it into a non-routine or a routine that’s better. This strategy is fraught with problems, as quite frequently when we encounter the cue, we’ll override our predecisions. That’s what happened to coach Dungee’s Colts when they were “in the big game.” Instead of relying on the habits that Dungee and the coaches had drilled into their heads, they starting trying to think too much and started trying to second-guess their training. It cost them time, and that time cost them the game.

Finding the Cue

Finding the cues that trigger the routines may be the hardest part. Sometimes the cues are easy – like a visit to the family. Other times, the cues are subtle and difficult to find. However, once the cue is clearly defined, it can be “marked” by our conscious brains in a way that allows us to tell ourselves, “Hey, I need to look at that before blindly continuing.”

Finding the cue takes some careful sleuthing and patience. Setting the flag on it – making it available for our consciousness – is the next big challenge. However, once that’s done, you’ve got a critical break in the flow and the opportunity to change the routing from the cue to the routine.

Breaking the Routing

Effectively, the back side of the cue is routing to the routine. Most of the time, this is automatic. Whatever the default routine is gets run automatically. With our flagging the cue – which can sometimes be difficult – we get a chance to make a conscious choice. If we find that a call from our mom causes us to mindlessly start to eat whatever sweets are on the counter, we can look for the call as a cue – and pick a different strategy. Maybe doodling can cure our need to do something else. If we can’t quite go that far, maybe we can change what we eat to be carrots. It may still be a mindless routine in the end – but at least it won’t have the negative effects that eating sweets will.

It’s the routing that is key. We’ve got to keep the flag on the cue, so we can interfere with the routing long enough for a new default to take hold. For that to happen, we’re going to need some positive feedback.

Feedback

What makes some habits stick and some fade away? That’s the interesting question behind the revival of Hush Puppies. They were introduced in 1958 and were on the verge of being discontinued for lack of sales when something strange happened. In New York City, Hush Puppies became fashionable, and they started showing up in dance clubs and on runways – leading to a revival in the brand. (See The Art of Innovation for more on Hush Puppies revival.)

The answer may lie in the corn fields of Iowa. Everett Rogers worked for Iowa State University, and his work with the farm extension led him to study how innovations were adopted by farmers. He noted five factors for an innovation to spread: relative advantage, compatibility, apparent simplicity (his was complexity, but I’ve flipped it here for consistency), trialability, and observability. (See Diffusion of Innovations for more on his work.)

His final factor is the interesting one, as it indicates that you need to be able to see the difference. When coupled with relative advantage, the ability to see the advantages you get is powerful. Hush Puppies might have become a status symbol (see Who Am I? for more on motivators, including status). However, most of our habits don’t fall into the category of status, unless it’s your morning cup of Starbucks coffee.

The ability to see the impact of what you’re doing is feedback, and it shows up everywhere as a key factor. Flow, Finding Flow, and The Rise of Superman all speak of the need for feedback to enter the highly effective mental state of flow. Ericsson speaks of the need for feedback – often candid feedback – in the development of peak performers in his book Peak. One of the key challenges that marketing programs face is the difficulty of getting good feedback to make informed decisions. Thinking in Systems (and to a lesser extent The Fifth Discipline) reminds us that delays in feedback can cause systems to be unstable. Effective and nearly immediate feedback has changed the way pictures are taken. Digital cameras provide instant feedback and therefore the ability to take pictures again – and learn from mistakes.

In learning, feedback is essential to anchoring the learning into the system. Immediate feedback – not during a test – can make learners dependent on that feedback and can prevent learning. However, in most cases, feedback is a critical component to effective learning. By depriving learners of effective and timely feedback, you can depress or even suppress learning. (See Measuring Learning Effectiveness for more.)

Effective feedback lies at the heart of improvement on many levels. Multipliers use feedback to help employees improve, while diminishers provide little or poor feedback, and as a result deprive people from growing. (See Multipliers for more.)

How Feedback and Rewards Differ

Duhigg calls the end of the cue-routine-reward cycle “reward”; however, the researchers he cites for his work use words like error, bias, and, more importantly, feedback. I’m willing to go out on a limb to shift away from Duhigg’s language, because his language doesn’t accommodate negative feedback. We can change behaviors by attaching tangible, short-term, negative feedback to a behavior. Feedback is a more encompassing word than reward that can take in the complexity of our brain’s decision-making. When we see the cue, we want to pick the behavior that has the best chance of the best reward.

Additionally, reward is an implied singular thing. Feedback can contain multitudes. There can be some positive and some negative feedback. We can net that out in the same way that we can consider all gravity to be concentrated at the center of an object. This center of gravity for feedback – the center of feedback – can shape whether it is more or less likely for a cue to route to a routine or not.

In my work and the work of others whom I trust, shifting the routing from cue to routine is THE key to making change.

Creating the Craving

Duhigg explains that we can get into a situation where we have a neurological craving for something. In this case, we can receive a shot of dopamine before we get the reward. Dopamine, though described as the pleasure drug, is beginning to lose its moniker. As we learn more about dopamine, we realize that it’s not the be-all and end-all of pleasure after all. It plays a role in pleasure and in learning, though the role isn’t as clear-cut as we once thought it was.

Duhigg speaks of Wolfgang Schultz’ work, and how neural activity spikes occur before the reward. However, it’s not clear what these spikes in activity mean. It’s possible that these are the result of mental models being built and run. In correspondence with Dr. Schultz, he indicates that the dopamine receptors may be getting information from the models about outcomes – though this is still unclear. (See Sources of Power for more on mental models.)

We do know that cravings are real. While addictions aren’t primarily based on chemical addiction, there is a neural processing component that drives the continued behavior. It’s not clear whether this is a neurochemically-based problem (a hardware problem) or a thinking problem (a software problem). There are some genetic markers for addiction susceptibility, but the gene doesn’t indicate that you will become an addict, just that it’s more likely. (See Chasing the Scream for more about addiction and No Two Alike for more about the role of genes and environmental interaction.)

Cravings, Duhigg explains, drives the cycle back from reward to cue again. Here, too, I disagree.

Open Loop

Duhigg draws the cue-routine-reward as a closed circle. I disagree with this representation, because the arrows don’t mean the same thing. The arrow from cue to routine could be described as “leads to” – so, too, could the arrow from routine to reward. However, it’s difficult to assign “leads to” to the arrow between reward and cue. I believe that this is because the real diagram is from cue to multiple routines – with connecting lines of varying thicknesses. The step after the cue, the routing, selects the best fit routine – which is the one with the strongest connection. (See Analyzing the Social Web for more on connection strengths.)

The issue is, I think, that Duhigg doesn’t have a representation of a routing component – the critical component – in his model. This is where the action happens and where changes both do and need to occur.

12-Steps

If you want a model of changing habits, a good place to look is 12-step programs, though they occasionally come under fire for a lack of demonstratable efficacy – and because they will allow people to exit on their own. However, arguably no other program or approach has helped as many people overcome their addictions. Why and How 12-Step Groups Work is the subject of a separate post.

Expectations

If you want someone to stick to a decision – to a change in behavior – how do you do it? In short, tell someone. Once you’ve told someone about a decision, it makes it less changeable. Once your friends, family, and community have been told of your intent and expect that you’ll follow through, the odds are that you will.

Our social drivers will not want to wade through the disappointment and the continual conversations of having to face everyone with the lack of change. In effect, we change the stories we tell ourselves and the stories that others tell about us. (See Redirect for more on the impact of stories on change.) It will often provide a firm push into the direction of making things happen.

Making It Visible

Telling someone of your intent is just one expression of the fundamental concept of making your changes visible. 12-step programs say that you’re only as sick as your secrets. The more you can make your thinking visible, the more likely you are to make the change. However, there’s another important role to visibility. By simply making things visible, you make it possible to evaluate things that you never realized might be happening.

Food journaling is an effective way to change eating behavior – because it makes it impossible to ignore the reality of how much food is being consumed. It is no longer possible for our memories to get intentionally fuzzy about that extra helping or the second cookie. It takes what our brains want to be invisible and makes it visible.

The Value of Failure

Failure, when it’s used to teach, can be valuable. Addicts often fail to “remain clean” their first time. They fall back into old habits. They get disconnected from their new support systems. However, successful recovering addicts learn what the trigger was, or what their hubris was, or what “got” them. They put barriers in place to prevent the same thing from happening again. Ultimately, this creates a situation where there are too few gaps for their old habits to sneak through.

Failure is only failure when you give up. Failure can be a powerful teacher as long as you don’t let the failure become fatal. We have to expect that, when we’re changing habits, we’re going to have some failures.

Hope

The most powerful force in the universe is hope. It’s what fuels our ability to get up after a failure. It’s what allows us to believe that we can make a change when no one else has. Hope broke the four-minute mile. Hope got us to the moon. Hope returned Apollo 13 home. The greatest thing that allows you to change a habit is the hope that you’ll be successful. That’s why 12-step programs are so important and powerful. They instill hope that you can change, because someone else has already done it.

It’s my hope for you that, if you’re trying to change your habits, you’ll find the answers in The Power of Habit.