Book Review-The Effective Change Manager’s Handbook: Essential Guidance to the Change Management Body of Knowledge

Ideally, there’s a body of knowledge that defines a profession. It’s what you should know if you’re a member of the profession. The Effective Change Manager’s Handbook: Essential Guidance to the Change Management Body of Knowledge seeks to be that for change management. While it goes far towards this end, it has the problems that all bodies of knowledge have – too much breadth but not enough depth. It’s a great way to learn about the things that the authors believe you should know but not enough to learn it. It also suffers from the biases of including some things that may not be necessary and missing other critical tools that effective change managers need.

A Tale of Two Organizations

A good starting point for understanding the body of knowledge is understanding that there are two organizations seeking to become “the” change management association that everyone belongs to. There’s The Association of Change Management Professionals (ACMP) and Change Management Institute (CMI). ACMP is organized out of the US, and CMI is out of the UK. They’re similar in their mission and quite different in their approaches. ACMP has “The Standard,” which identifies the standards that change professionals should understand. It’s not quite as prescriptive as it sounds, but it’s definitely a process-driven model with steps and artifacts.

CMI, on the other hand, is focused on the body of knowledge, which is more of a collection of things than a process or approach. They initially published the body of knowledge as a separate volume before allowing it to get collected up into The Effective Change Manager’s Handbook.

Both organizations offer certification as one would expect, and both offer training, though CMI has chosen to only endorse training from one provider. I personally believe this is a very bad move, because it constricts the industry by limiting the trainers who can become certified to teach about change management. However, both organizations are fundamentally focused on increasing the awareness of the discipline which is a good thing.

A Body of Knowledge

The idea of a body of knowledge was popularized by the Project Management Institute (PMI) and their PMBoK. If you’re Project Management Professional (PMP), then you’re walking around with the PMBoK as a sort of Bible. PMPs are certified by the PMI as project manager. After a few decades, the certification is recognized and has value if you’re looking for work as a project manager.

However, even PMPs will criticize the PMBoK, because it isn’t always practical. Because it has everything in it, it’s too heavy for all but the most massive super projects. Historically, it’s been focused on waterfall-type projects, with one start and one end. It’s also been focused on projects that are more algorithmic and less heuristic. That meant that it didn’t work well for software development projects.

The PMBoK faced real pressure in software development, first with CMMI thinking and more recently with agile (iterative) approaches. It took many years before the PMBoK acknowledged the validity of these approaches.

Thus, there are two problems with a body of knowledge – first that it’s too exhaustive. It’s more than anyone would ever use. Second that it’s non-inclusive: the good practices are excluded for a long time after they’re useful.

In the case of The Change Manager’s Handbook, there’s a lot of the former and only a little bit of the latter.

In Full Bloom

Benjamin Bloom and his colleagues set out to explain a hierarchy of learning objectives. The idea was to come up with a way of explaining and categorizing the differences in approaches to teaching and learning. Though they never really finished, their start was the completion of the cognitive domain of learning. As a result, we have an ordered hierarchy of learning objectives, from the very low-level awareness and recall to the very high-level synthesis and creation of new knowledge in the domain.

Most of the time, educators and learners shoot for somewhere in the middle. They want to be able to apply what they’ve learned and analyze a situation based on their knowledge. However, works on a body of knowledge almost always fall short of this spot. They’ll create awareness, recognition, and sometimes recall, but rarely do they help people apply the learning.

That is the case with The Change Manager’s Handbook. It’s like a listing of the things that you need to learn without the depth or the examples that lead to the ability for someone to apply the information. If you’re looking for an overview of what skills you need as a change manager, it’s great. If you’re looking for a guide for doing further research, it’s good. If you’re looking for something to teach you what you need to know and how to use it so that you can be an effective change manager, well, it’s not so good.

Change Management Successes

It’s been widely quoted that 70% of change management initiatives fail to deliver. (See Leading Change for John Kotter’s take.) With the exception of professional baseball, those statistics are awful. Who wants to think that two out of three change initiatives they work on are going to fail? No one, obviously. That’s what the profession of change management and the development of the body of knowledge is designed to solve.

Some, like William Bridges in Managing Transitions, even suggest that change is the wrong way to think about the initiative. Change doesn’t, he believes, properly recognize the human component and the losses that we encounter, personally. While most people still use the word change rather than transition, the point he makes about change being about people isn’t lost on those who are interested in success.

The size of the initiative had a great deal of impact on the probability of success. The larger the project, the less likely it is to be successful and the greater effort and skill that will be required to make it successful. This is the same as the PMI’s guidance regarding projects. Everyone is clear that the problem of success gets exponentially harder based on the scope and scale of the effort. As a result, one of the big considerations for change management success is how you frame your project and how you break it down, so that you can accomplish a series of smaller changes and build on those wins.

Motivation

To accomplish change, you need to motivate others to join you in the journey of change, and that requires motivation. However, the research on motivation has had a checkered past. Back in 1968, Fredrick Herzberg wrote an article, “One More Time, How Do You Motivate Employees?” for the Harvard Business Review. It turns out it’s the most requested article reprint of all time. How can it be that an article with such a snarky title can be so popular? The answer is in the insight Herzberg shared that the things we think of as motivators aren’t all as motivating as we think.

Some things that we think of as motivators Herzberg have an element of what he called “hygiene.” That is, once you had enough of them, the addition of more had little impact. The other aspect was motivation. Each of the things we think of that motivate people are built from these two components. Effective change is knowing which is which. When dealing with a hygiene-based motivator, when do you know how to stop and try different approaches.

It turns out that the go-to motivator of compensation turns out to be mostly a hygiene-based motivator, and salary after a certain point isn’t that powerful a motivator. This aligns with both the work of Kahneman and how we have decreasing utility for increasingly large benefits. (See Thinking, Fast and Slow.) It also aligns with the work of Edward Deci on intrinsic motivation, but Deci goes further to explain how increasing salary can make the behaviors worse.

Intrinsic Motivation

Studying what makes people want to do something is interesting and challenging. Deci ultimately discovered that our intrinsic motivation is driven by our desire for autonomy, mastery, and purpose. These factors drive us towards wanting to do something. However, there’s a challenge: if we apply an extrinsic motivator – like compensation – to something that we’re intrinsically motivated to do, we may find that the intrinsic motivation is stunted. When children were paid to play with a toy that they previously enjoyed playing with – without compensation – they suddenly wanted to play with the toy less when they weren’t compensated.

This has huge implications and obvious evidence all around us, we just have failed to see it. Take, for instance, children. They love to study, and you reward that studying with some sort of monetary compensation for grades. Maybe $1 for an A and $0.50 for a B. The problem is that you’ve now made the motivation dependent on the extrinsic reward. What happens when the reward is taken away? The behavior stops. More challenging is the fact that the long-term pull of the intrinsic motivator may be more powerful than the extrinsic one. Consider Simon Sinek’s recommendation to Start with Why and the power of getting everyone aligned to the same mission.

But what about flow? Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi researched this state of balance between challenge and skill that seemed to be intrinsically rewarding and discovered a set of factors that lead to it – as well as some of the far-reaching effects. Flow is internally rewarding. We don’t do it because others ask us to or that we’re being compensated for it; we enter the state of flow because it’s rewarding. It’s substantially more productive than normal work (5x), and it induces a sense of timelessness. The focus on the task eliminates some of the normal background noise that flows through our head. (See Flow, Finding Flow, and The Rise of Superman for more on flow.)

Ultimately, our goal as change managers shouldn’t be to find the magic external motivators that will allow us to manipulate others into doing what we want them to do, but rather to look towards the goal of how we can align their internal motivators in ways that support them wanting the same things the organization wants. (See both Why We Do What We Do (Deci) and Drive (Daniel Pink) for more on intrinsic motivation.)

Our Views on People

There are two basic views of people. We can either assume that people are lazy and stupid – or we can assume that people are intelligent and hardworking. These correspond to the Theory X and Theory Y of management that we’ve heard about. Historically, most management was designed around the idea that people were lazy and stupid. However, more recently, it has been recognized that this isn’t necessarily the best approach.

Consider, for a moment, the communism vs. capitalism debate that occurred in the 20th century. The Marxist ideas drove the creation of societies based around the idea that everyone was entitled to basic rights and the government was responsible for providing these to everyone. The result was a top-down, centralized hierarchy that depended upon the masses as hands to move and create things, but only those things that the hierarchy told them to make. The problem was that this approach, noble as it was, failed miserably. People were deprived of their drive and creativity, and as a result, there were many economies that were ruined and people who suffered with a lack of essentials because the society couldn’t produce what was needed for everyone. (See One Minute to Midnight for some exposure to this problem.)

The transformation that is happening in business has been gradual but pervasive. Carl Rogers believes that you should have an unconditional positive regard for all people, and that’s hard to do if you fundamentally see them as lazy and stupid. (See A Way of Being.) The list of books I’ve reviewed that have a focus on seeing people differently isn’t short: An Everyone Culture, Reinventing Organizations, Red Goldfish, Leadership for the Twenty-First Century, Seeing Systems, Multipliers, Creativity, Inc., Servant Leadership, and more.

Views on Organizations

While our views on people have changed, at some level, we’re also reconfiguring our views on organizations. We’re starting to look at them less like machines with interchangeable parts and instead we’re looking at them like they’re organisms, brains, cultures, and other structures that describe pieces that come together as a whole – but don’t fit neatly into the kinds of gears and mechanisms you would expect to find in a machine.

However, some of the views of the organization can be troubling. When they’re viewed as psychic prisons or instruments of domination, the resulting expectations don’t lead to good places. There’s a lot that can be said of prisons and Phillip Zimbardo – of the Stanford Prison Experiment fame – describes his perspective in The Lucifer Effect. From a more positive perspective, Amy Edmonson explains in The Fearless Organization how to avoid the kinds of organizations that feel like psychic prisons.

Two Voices

Sometimes the person that sends the message impacts the message that is received more than the words or actions used. When it comes to change, there are two key messages and two key people who need to send the message.

The first message is the strategy and the organization’s vision. This message is best delivered by the executives. It’s believable when delivered by the organization’s executives – it isn’t necessarily believable from a person’s direct manager.

Conversely, what people need to know about their role being okay and how it will change comes from their managers. Anything that the executives say in this regard is perceived to be a platitude that will change just as soon as it’s convenient. Employees need the relational context that they have with their manager to accept the message of safety that may be provided to them. Despite the best intentions, a manager speaking about the overall strategy for the organization isn’t believable, because the employees have seen their best intentions get run over before.

VUCA

In the 1990s, the US military started speaking in terms of VUCA – Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity. We live in that VUCA world. The rate of change isn’t slowing down, by all measures it’s getting faster. It’s not just the changes that you want – it’s the changes that are happening around you.

A set of responses to the VUCA world that we live in were proposed by Bob Johansen and are referred to as VUCA’ (or VUCA Prime, as in inverse derivative): Vision, Understanding, Clarity, and Agility. These are excellent characteristics of your change initiative. Developing a clear vision and communicating clearly based on your collective understanding of the world and the changes is a great start. The agility to adapt as you learn more and as the situation evolves improves your chances for success.

Heroic Leadership

One of the most powerful things that I learned from Heroic Leadership was to separate the important from the unimportant. The Jesuits were clear about their faith and the things that were required of them to remain in their faith. They were equally aware of the customs and rituals that they had grown comfortable with. Knowing how to separate these two proved invaluable as they navigated new worlds.

There are some things inside a change initiative that are going to be non-negotiable. However, most things are open to discussion and exploration. Few things in any change are truly beyond our ability to evaluate.

It Starts with Strategy

The truth is that all change is the response to the environment we find ourselves in. Either we believe that we’re able to take advantage of an opportunity, or we feel the need to mitigate a threat. This response to the environment – or, more likely, the set of responses to the environment – is collectively our strategy for navigating the real world that the organization and we live in.

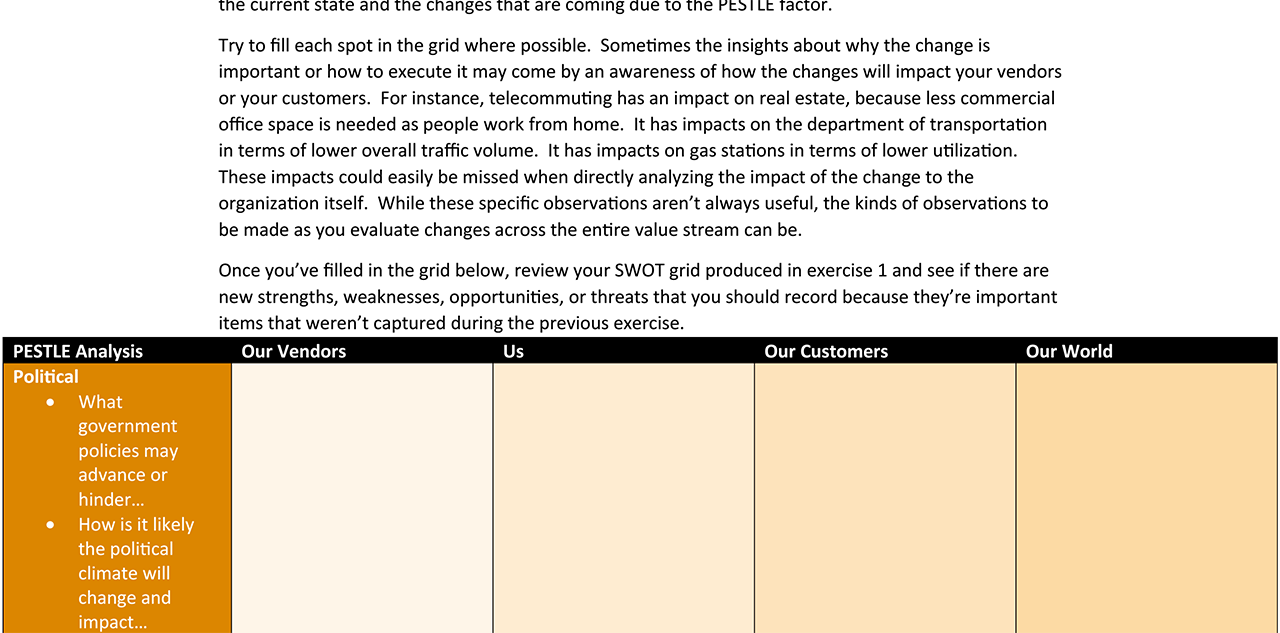

If you’re going to initiate any kind of a change, you’ll need to understand both the factors that are driving the opportunity or threat and what strategies – or tactics – you believe you need to use to capitalize on the opportunities and mitigate the threats. In short, your change starts with clearly understanding your strategy and the environmental factors that have led you to the proposed approaches.

It’s All About Behaviors

All change is individual change. Organizations change through the actions – behaviors – of its members. There is no changing the organization without changing the behaviors of the members. Thus, all change is individual change. All change is about how you change the behaviors of individuals in ways that creates the kind of change you want to see from the organization. If you’re not converting the big-picture strategies into the individual tasks and behaviors, it’s not very likely that it will be successful.

Transmission

I worked very hard, and when I turned 25, I bought myself a Mitsubishi 3000GTVR4. It was a low, wide, heavy, and, in many ways, amazing car. The engine was 320 horsepower, and it was all wheel drive. It was a monster of a car with a problem. The transmission had a habit of breaking. The torque the engine produced would throw you back in your seat, and in the process, it would weaken and eventually break the drive shaft. The result for me meant more than a few transmission repairs. The engine was fine, the tires were fine, it was just getting the power between the two that was the problem.

This is the key issue that most organizations face. They have a strategy, but they don’t know how to convert it into something that will cause people to change. Some of that can be based on having too few people involved with the development of the strategy and, as a result, a limited amount of buy-in. It can also be caused by unrealistic expectations about how the organization functions.

Whatever the cause, if you can’t convert the strategy to the behaviors, you won’t see change.

The Wisdom of Crowds

One approach to address this transmission problem is to involve a large number of people in the planning process. While this does create challenges about giving everyone space to feel heard and the need to coalesce the responses into a set of key approaches, it has the benefit of substantially increasing buy-in. When done across the organization, you can develop a greater buy-in within the organization. However, you get something more. You get the wisdom of crowds.

If I asked you to guess the number of jellybeans in a jar or the weight of a bull, it’s likely that your guess won’t be exactly right. You’ll overestimate or underestimate. That’s not news. The news is that, as you add more and more people with their individual biases together and you average them, you begin to get to answers that converge on the right answer. Somehow the process of averaging takes the errors and biases out of the process, and the result is better. That’s what happens when we involve more people in our change process. We begin to work past the biases and errors. We move towards a wisdom about the situation that can’t be developed by a single person. (See The Wisdom of Crowds for more.)

Stakeholder Categories

George Egan recommends putting stakeholders into the following groups:

- Partners are those who support your agenda.

- Allies are those who will support you given encouragement.

- Fellow Travellers are passive supporters who may be committed to the agenda but not to you personally.

- Fence sitters are those whose allegiances are not clear.

- Loose cannons are dangerous, because they can vote against agendas in which they have no direct interest.

- Opponents are players who oppose your agenda but not you personally.

- Adversaries are players who oppose both you and your agenda.

- Bedfellows are those who support the agenda but may not know or trust you.

- Voiceless are stakeholders who will be affected by the agenda but have little power to promote or oppose and who lack advocates.

I prefer a slightly different categorization process based on power, urgency, and legitimacy, but this approach encourages you to more deeply consider and understand your stakeholders and whether they collectively bring you what you need to accomplish your objectives with the change.

Control and Manipulation

In Compelled to Control, J. Keith Miller explains that we all want to control, but none of us want to be controlled. This is a fundamental understanding of our human condition. We want to perceive a great deal of control of our situation and a low degree of others controlling us. As we seek to involve more people, develop their buy-in, and engage them, we must be conscious both of their need to feel a degree of control but also in the degree to which they perceive that they’re being manipulated.

We are all manipulated. An easy example is the fact that almost all of us wear seatbelts. No one thinks that wrinkled clothing and confinement is good, but we’ve been conditioned to accept these things so that our chances of injury or death during an accident are reduced. We’re being manipulated into the behaviors that the government wants with laws and advertising campaigns. It’s not that the reasons aren’t the right reasons or that we shouldn’t wear our seatbelts – we absolutely should. However, we need to recognize this for what it is. It’s a manipulation of our basic behavior while driving and riding in a car, and it’s a manipulation that we’ve accepted.

Put the Song on Repeat

The process of manipulation was subtle. It was the same message played over and over again punctuated by changes. This process of manipulation can be done for both good and evil. Albert Bandura in Moral Disengagement explains how Nazi Germany made the unthinkable not just something to be considered but something to be done. It wasn’t just one message that the Jews weren’t humans, it was the same message over and over again.

In our corporate change worlds, we like to believe that we can tell people once and that’s enough. They read their email, we think. They’ll see the posters. The truth is, however, that our communications are far less effective than we’d like to believe. The Organized Mind explains how our brains are trying to cope with the amount of information that we’re getting, and for the most part, we’re doing it by filtering. If we can’t get through the filter, then there’s no chance of anyone changing their perception (or even awareness).

A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words

It’s an old cliché, but it’s true. A picture, or more precisely a diagram, is worth a thousand words. The ability to convey visually what the new organization will look like and what the behaviors are that will be required is extremely valuable. It’s more than an updated organizational chart. It’s about what life will really be like. It’s a way of engaging emotions into topics that are sometimes dry, abstract, and analytical.

The simple addition of visuals to your change messaging can make them feel more personal and friendly. Careful selection of a metaphor can provide some continuity to the discontinuity of change.

Making Use of Micro Signals

During change, people will need more affirmation and confirmation that their behaviors match the new trajectory of the organization. For that reason, small acknowledgements of the progress that is being made to transform the organization is critical to reinforcing the new behaviors and helping to establish them as new habits.

Accentuating “bright spots,” those places where people are exhibiting the best of the new behaviors, help others understand that they want to replicate these behaviors. In the book Switch, Dan and Chip Heath make the point that following the bright spots can help people make a change much easier than simply guiding them away from the things they should not do.

The Importance of Learning

The importance of learning as a far leading indicator was made by Richard Hackman in Collaborative Intelligence, but its use as a tool for change is sometimes overlooked. We forget that new behaviors mean new learning, and the more that we can instill learning into the culture of the organization, the more agile the organization will be. Learning is a powerful force when lined up with the compounding nature of sustained effort.

Einstein said that compounding interest was the 8th Wonder of the World, but it’s not just financial interest that compounds; learning and our ability to learn compounds as well. The more we’re willing to focus on our performance and seek to improve it, the more our performance will improve. Anders Ericson and Robert Pool explain in Peak that it’s purposeful practice that makes the difference to our long-term success. The more willing and persistent we are at practicing towards specific goals, the more likely we’ll be at the peak of our industry. (For the persistence aspect, see Angela Duckworth’s Grit.)

The Hawthorne Works are famous for the Hawthorne effect. That is, measuring people – not the actual change being measured – is responsible for improvement. However, this obscures the truth that people are focused on their performance because they know they are being watched. This pushes them into purposeful practice and an attempt to improve their performance. That focus does increase their performance even when the conditions deteriorate (like the lighting being turned down).

When you sustain the perception of monitoring and a desire for improvement over a long period of time, the improvements become staggering. In The Rise of Superman, Steven Kotler explains that even a 4% increase over a long period of time makes it appear that what the person is doing should be impossible.

Our View of the Problem is the Problem

When we’re evaluating why our change initiatives haven’t been successful, it’s important to accept the realization that our view of the problem – the change itself or the problem the change is designed to address – is the problem. The better we understand a problem and the more we know, the more equipped we are to potentially solve the problem. That’s the reason why it might be a good idea to read The Change Manager’s Handbook.