Now Available: Organizational Readiness for Generative AI Draft White Paper

The Cold War Experience

Vacations for us are often about the experiences. It’s about sharing with our now adult children what things were like in the past or what they are like in the present for different people. Our recent vacation was anchored around “The Bunker.” It’s a relic of the Cold War situated in the Allegheny mountains, and it’s a secret that was kept successfully for 30 years. As we went through the facility, I realized that our children couldn’t connect the experience to what it was like in the Cold War. This post is an attempt to weave together enough context that everyone can understand what might make the government secretly pour 50,000 tons of concrete into a facility that wasn’t designed to sustain a direct nuclear attack.

From Allies to Enemies

The transition from allies in World War II to enemies in the Cold War was predictable. The United States was capitalistic and independent. The Soviet Union was based in Marxist ideas of communism, central planning, and obedience. From an ideological standpoint, it would have been hard to draw to more divisive positions. With a common enemy, we could side-step our ideological differences, but without that, we would eventually begin to vilify the other. We’d find a new enemy to hate where we once saw an ally.

This presented a nuclear problem. The United States initiated the world to the atomic age with the bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki that ended World War II in the Pacific. Shortly thereafter, Russia developed their own atomic bombs; after that, both sides developed even more powerful hydrogen bombs. Suddenly, there was enough power to cause major havoc.

The Escalation

The Cold War escalated through numerous microaggressions on each side. A game of nuclear one-upmanship started and just kept going. While we know now that capitalism was more effective economically than the Lennon-Marxist approach that the Soviet Union was based on, back then, both sides were posturing to have the upper hand. The world agrees that the closest that we ever came to nuclear war was the discovery of missiles in Cuba.

The United States had medium range ballistic missiles deployed in Turkey – a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) country – that would reach Moscow. It was about 1,200 miles – the same distance between Cuba and Washington, DC. However, for the United States and John F. Kennedy, it felt more personal. The event was called the Cuban Missile Crisis, and it’s cataloged in One Minute to Midnight (among other books). It’s the closest we ever came to activating the project that eventually became named “Greek Island.”

Escaping Fallout

The Soviet intercontinental ballistic missiles of the time weren’t very accurate, and, little did we know, there weren’t very many of them. However, the threat of attack was real. The Soviets could launch an attack that would require the evacuation of Washington, DC, and there would be at least some warning of the attack. There was no question in anyone’s mind that Washington, DC was on the “hot list” for the Soviet Union. It was expected that Washington, DC would see a nuclear missile. The idea was that if Congress could survive the initial attack, they’d need a place to go to continue the operation of the government – and that was “Greek Island.”

The government needed a facility that was close enough to Washington, DC to be reachable, yet far enough away that the fallout from the radiation wouldn’t be a problem. The result was a small town in the middle of the Allegheny mountains, 240 miles from Washington and relatively protected from airborne attack – the kind of attack assumed to be the most likely way that a secondary location might be targeted.

Duck and Cover

Meanwhile, school students were being taught to duck and cover under their desks in the event of an air raid. Somehow, the London bombings from World War II had become lodged in the hearts and minds of the planners and was coupled with the fact that we used planes to deliver our atomic arsenal on Japan. The assumption was that, if war ever did break out with the Soviet Union, it would come in the form of an aerial attack.

The student desks at the time were neither impervious to conventional bombs nor nuclear ones, but somehow these drills helped reinforce both the ability to take some action and a trust in a government that was there to protect you.

At the same time, fallout and bomb shelters were being constructed by individuals of means and communities of concerned citizens. The threat of bombings and nuclear war was perceived to be eminent for decades. The argument was that one of the skirmishes that the United States and The Soviet Union had been supporting would eventually spill over into an all-out attack, and everyone wanted to be ready for it.

While the fallout and bomb shelter business may have been commercially profitable for some construction companies, relatively few community shelters were developed and stocked. However, it reinforced the idea that the country had a plan and we were ready.

The Greenbrier

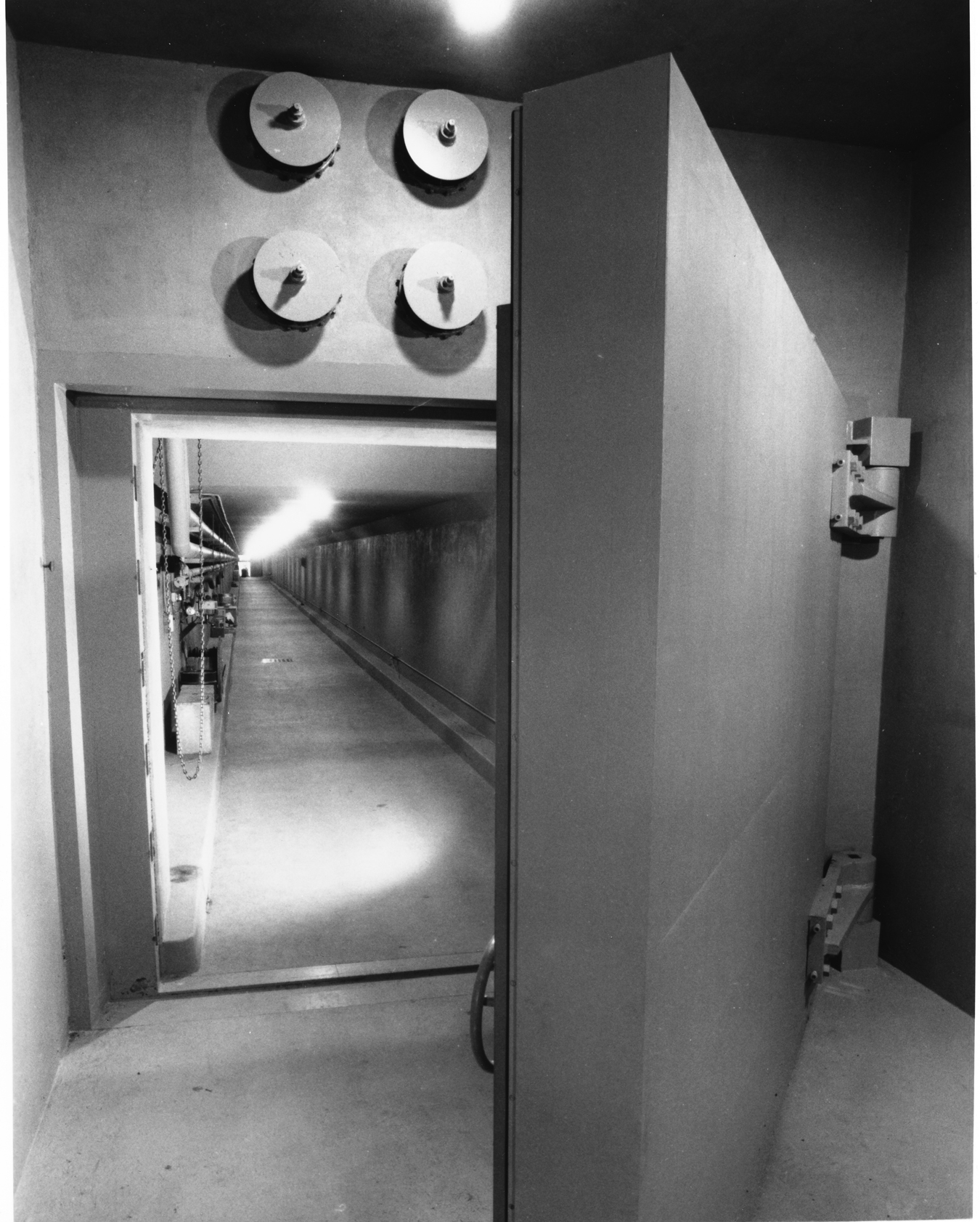

Located in the Allegheny mountains about 240 miles away from Washington, DC, accessible by railroad, car, and airplane, The Greenbrier hotel was an ideal place for Congress to go in the event of a nuclear emergency. However, the hotel’s luxurious amenities weren’t what Congress was going to need. They needed something a bit more primitive but much more concealed and self-contained. They needed a bunker that could protect Congress from the fallout of a nuclear war even if the facility couldn’t sustain a direct hit.

The facility was owned by the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, an organization that the government was already in the habit of writing large checks to. Adding some additional funding for a secret underground bunker wouldn’t be that difficult.

The Construction

You can’t hide the construction of a bunker, even in the late 1950s. People were going to know that something was up. So, a cover story was created. The cover story was the expansion of the hotel with subterranean event space. The construction was divided up to different people with the idea that, if the work were divided sufficiently, few people would be able to put together the true scope. Those who worked more closely were given “the talk” about national security, secrecy, and ultimately a non-disclosure agreement to sign.

Construction was completed in 1962 – the same year of the Cuban Missile Crisis and the only time in its history that the bunker was almost used.

Operational Status

For 30 years, until its existence was revealed in 1992, the bunker was kept operational ready by a government contractor, Forsythe, whose cover story was that they would repair the TVs and communications at The Greenbrier. They did this in addition to their real duties maintaining the infrastructure that would hum to life in the event that a confidential lease was activated.

With a phone call indicating that the government was activating their lease, The Greenbrier would provide three days’ worth of food to supplement the non-perishable and semi-perishable food that would already be in the facility – stocked by government contractors. In the hours that followed, members of both houses of Congress would arrive, and once the Congressmen and their staff had arrived, the doors would be sealed, and the bunker would be isolated except for communications.

The Reveal

The secret was safe for 30 years, until, in 1992, the existence was revealed in The Washington Post. Arguments are still had today about whether its disclosure was a good or bad thing. The original mission as a Cold War bunker for Congress no longer held. First, attacks had warning times of minutes, not hours any longer. Second, in December of 1991, the Soviet Union had officially fallen apart. Russia and several other states were going to have to go it on their own. The Russian threat was gone.

The details of Project Greek Island were so secret that even the very members of Congress, who were to be protected in the bunker, were unaware of its existence. Suddenly, what was a secret to even those whom it was designed to protect was revealed, and because its safety was now compromised, it was decommissioned.

The Greenbrier operates tours now, taking people to places to parts of the bunker that remained hidden for 30 years. However, you’ll need to leave your camera and cell phones behind. No electronic devices are allowed – but not because of the government, at least not directly.

CSX-IP

We were told on the tour that the reason we can’t have cameras, phones, or any electronic devices was because of the company operating in the space, CSX-IP. They were described as a company that secures data for Fortune 500 companies. However, there are some oddities in the story that just don’t add-up.

The C & O Railway, which owned The Greenbrier, was gobbled up by the rail giant, CSX. CSX-IP makes some sense in that they were some data spin-off or subsidiary of CSX. Except the official paperwork files with the state of Florida lists CSC as the corporate parent. CSC eventually became DXC. DXC doesn’t list CSX-IP as a subsidiary. Neither does CSX, by the way.

So, where do their clients find them? CSX-IP doesn’t have a web site. They’re an IT company running data services for Fortune 500 – but they don’t have a calling card on the internet.

If there were a data center operating in The Greenbrier, it would justify the diesel tanks and electrical generators that are maintained. It wouldn’t justify the water tanks that are maintained as well – though that’s attributed to the culinary school that is in operation. (Which wouldn’t justify this amount of water.)

Space Saving

If you had a data center operating in the bunker, it would justify blocking off space. On the tour, we didn’t get to see much space. There were the rooms for decontamination, the cafeteria, and the meeting room for the House of Representatives – but not the meeting room for the Senate. Nor did we see any of the dormitory rooms. In short, we saw a small fraction of the space that we should have seen. No explanation was given for the huge amount of space that we weren’t seeing.

However, what’s more interesting to me is that there’s a power and cooling problem that wasn’t addressed.

Power and Cooling

The real problem with data center design is power and cooling. As computer density has gone up, so have the power and cooling requirements per square foot. So, a single rack will consume between 7kVA to 60kVA of power. The net result is an expectation of 200 watts per square foot to as much as 400 watts per square foot. Compared to an office, that would have power consumption at about 1/10th of those numbers.

All that power gets converted into heat, and that heat must be cooled by something. That’s generally done with air conditioners that have heat exchangers outside the serviced area. That’s 10 times as much cooling as initially planned – and I didn’t see anything approaching that.

Conspiracies and Psychology

Perhaps the most interesting thing about all this together is that The Bunker was designed from the outset with psychology in mind. From the blast doors hidden behind “noisy” wallpaper to discourage loitering to the colors and patterns, everything was designed to obscure what was really going on.

At the end of the day, wouldn’t it be amazing if The Bunker hadn’t really been shut down in 1992 as was officially reported? What if it were still being maintained today not for its original Cold War purposes but for purposes like protecting Congress in the event of a terrorist threat – or maybe even a global pandemic?

If you want to see for yourself, schedule a tour of The Bunker.