Robert Bogue

June 18, 2018

No Comments

I’ve read much of Brené Brown’s work, but it wasn’t until I read I Thought It Was Just Me (But It Isn’t): Making the Journey from “What Will People Think?” to “I Am Enough” that I made it back to the beginning. I had previously commented in my review of The Gifts of Imperfection that I was reading her work in non-sequential order and how that can sometimes be disorienting. I had already read Daring Greatly and Rising Strong (my review is split into part 1 and part 2). Despite having read some of Brown’s later work and some of the references she uses, I Thought It Was Just Me (But It Isn’t) still had things to teach and remind me.

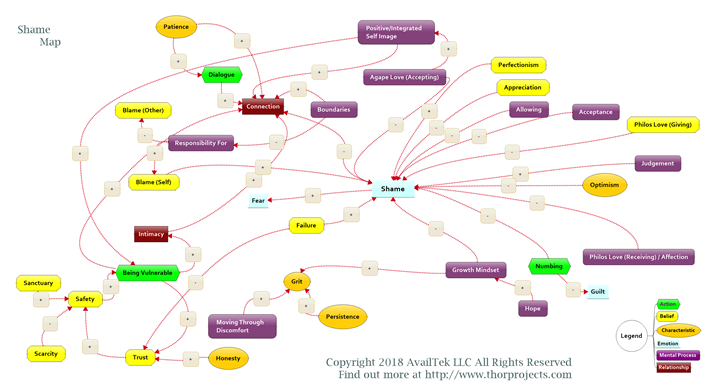

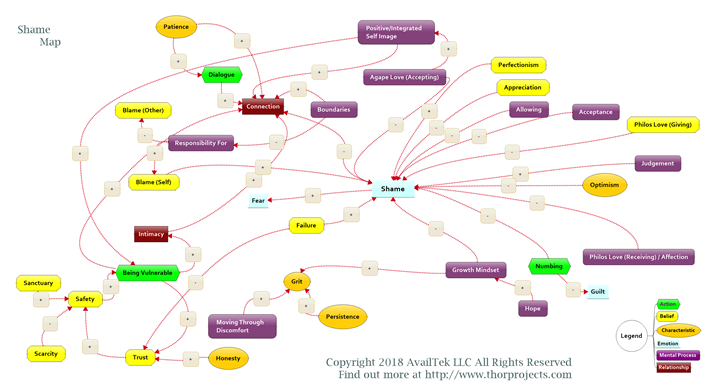

As a sidebar, the book was initially self-published by Brown in 2004 with the title Women & Shame: Reaching Out, Speaking Truths, & Building Connections. It was 2007 when Penguin bought the rights and released it with this title. I’ve taken some of Brown’s work here, put it together with pieces from other resources, and created a shame map:

Shame Researcher

Brown frequently describes herself as a shame researcher; that is, she seeks to understand shame. Along the way, she’s clarified that guilt is someone feeling that they’ve done something bad, and shame is a separate emotion where people believe they are bad. Brown believes that shame separates us from one another, and it’s this separation that makes shame so particularly toxic to our being.

Shame is a self-sealing proposition. As shame disconnects and silences us, our shame becomes a secret, and secrets are where our mental sickness festers. The challenge with shame is the feeling itself makes it unsafe for us to share the shame with others. It erodes our trust in ourselves and others.

Beyond the definition of shame and cataloging experiences of shame she has sought to identify those skills and temperaments that make folks more resistant to shame and there by to live a happier and healthier life.

Connection

Before we can confront shame for what it is, we must acknowledge the truth that life is about connection. We’re inherently social creatures. We’ve been designed to be in community, and we experience psychological pain when we’re isolated and removed from every kind of human connection. Loneliness explains the lack of connection and how it differs from the physical state of being alone. The Dance of Connection speaks about the need for and the way to get connection. Dr. Cloud describes the need for connection – and healthy connection – in The Power of the Other as being core to our human condition.

When we accept that connection is essential to our human condition we can realize that shame has the power to separate us from others through our fear. If we ourselves believe that we’re bad and therefore unworthy of connection, isn’t it realistic to expect that others will believe that we’re not worthy of connecting to? That’s our ultimate fear: that we’ll be excluded from the group. (See The Deep Water of Affinity Groups for more on exclusion.)

Fear

I attribute most of my shame resilience to stealing fear as a basic component from it. It was years and years ago when I decided that I wouldn’t live in fear. I’m not saying that I won’t be afraid, everyone experiences fear from time to time. What I’m saying is that I made a conscious decision to not live in fear. If that meant that I made financial choices so that I wasn’t in debt, and the consequences were a beat-up car, a small house, and modest clothes – then that’s what it meant. I realized that my first concern was going to be not allowing fear to build a stronghold in my life.

Over the years, as people have attempted to shame me, I’ve resisted, in part because I refused to accept the fear of disconnection. I would confront the fears directly and speak with people about what was real and what wasn’t real. I’d use my friends like a GPS system to triangulate my real position. (See Where Are You, Where are You Going, But More Importantly, How Fast Are You Moving? for more on this idea.)

Fear is an essential component for shame, and without it, it’s like starving a fire of oxygen. Eventually, it will go out. Not immediately, not without a fight, but eventually it will yield.

Courage

Courage comes from the Latin root word cor, which is “heart.” In its earliest forms, courage meant “to speak one’s mind by telling all one’s heart.” We’ve lost this definition with our focus on courageous acts, which are framed around charging into burning buildings and taking great personal risk (altruism). However, courage in its purest sense is the ability to work through the fear of being rejected for who you are to defend people or ideals that you hold dear. (Look here if you want to get clear on the distinctions between Sympathy, Empathy, Compassion, and Altruism.)

Notice that courage requires fear. You can’t be courageous without vulnerability – and thus some fear. Vulnerability comes in the ability to be hurt. Without vulnerability, there is no fear and no courage.

Vulnerability

Why would anyone want to allow harm to – possibly – come to them? What possible motivation could someone have to become vulnerable? In a word: connection. Without vulnerability, there is no connection. Without our ability to share an unvarnished, unprotected part of ourselves, there’s no way that someone can get close to us. Wearing a suit of impenetrable armor also makes it impossible for someone to touch you – to connect with you.

Vulnerability in our relationships with others isn’t a binary thing. We don’t one day wake up and say to ourselves, “Today is vulnerability day.” Instead, we choose how much we share with others, how much we let them in and let them see us, warts and all. Often, we do this slowly, as we send over little test balloons. He might not like me if he realizes I’m saddled with debt, so maybe I can whine about my car payment and see how he reacts. She thinks that I have my act together. I wonder how she’d react if she knew I’d been in counseling for depression for years. Maybe I can suggest drinks at that bar “right next to the counseling center” and see what happens.

As we are vulnerable and aren’t attacked, we can open up to more to places and ideas that we’ve not yet broached. Each bid for connection – another way of thinking about being vulnerable – that is met with a positive response opens us up for more. (See The Science of Trust for more about bids for connection.)

Vulnerability may have a purpose and a need, but that still doesn’t make it easy. The process of being vulnerable to build trust takes time to build and a moment to lose.

Perceived Safety

In walking around in cities that I don’t know, I’ve probably walked into neighborhoods that I wasn’t really safe in. I probably shouldn’t have been there alone – or there at all. However, in most cases I felt fine. I was being vigilant about my surroundings, and things were fine. The funny thing is that one of the places that I can remember feeling the least safe was in downtown Manhattan. I couldn’t tell you where exactly I was, but I can remember the thing that triggered the feeling. It was the graffiti on the steel, roll-down doors on the shops.

Intellectually, I knew that there were uniformed officers a block away, leisurely chatting. They weren’t actively or intently scanning their environment. They seemed pleased that they had received such an easy assignment. However, I couldn’t shake the feeling that I wasn’t safe. I started processing the fact that these shops needed these steel doors. I started to process the bravado required to mark the doors. I had fallen for what Malcom Gladwell described in Blink as “broken windows.”

There are times when we feel safe when we are not – and distinctly, there are times when the opposite is true. When it comes to our willingness to be vulnerable – our willingness to walk into a new neighborhood – it’s our perception of safety that is important. Strangely, our perception of safety may have been shaped years ago in our childhood. How Children Succeed explains the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study, and how if you were exposed to adverse childhood events, you’ll be more cautious and reserved as an adult. You’ll be predisposed to not be vulnerable, because your perception of safety will be lower than most people.

Conversely, people who have a high degree of inner safety – which they had to develop – will take risks that no sane person should. (I may resemble this remark at times.) For these folks, there’s very little reason to spend energy protecting themselves, because they don’t believe they can be harmed – they don’t perceive their safety to be in jeopardy.

Clearly, there’s a balance here. You can’t have your set point for safety set too high, or you’ll step out in front of a beer truck and get flattened; but being so afraid that you can’t leave your home is also dysfunctional. We need to have enough safety to be vulnerable in a world with sympathy suckers.

Sympathy Suckers, Empathy Engagement, and Compassionate Connection

Sympathy is about separation. It’s an acknowledgement that things look bad – for you. The person who throws the blow-out pity party of the year is looking for someone to acknowledge their pain. That’s fine – as long as they, at the same time, don’t insist that you can’t understand. If you want someone to come alongside of you and invest themselves in your experience, you can’t tell them that they’ll never get there or, worse, make it impossible for them to get there.

Sympathy suckers want the energy associated with sympathy and don’t realize that it’s not a connection. It’s pity. The result isn’t two people getting closer together, it’s two people getting farther apart. A healthier approach is to seek and accept empathy. This is a simple expression of “I understand this about you.” It isn’t to say that one person understands everything about the other. It’s simply that there’s an aspect of your experience that I understand. I’ve never lost a child, but I’ve lost a brother, and I can use that tragic event to connect with others who’ve experienced a loss of someone close to them. I can demonstrate my compassion through my attempt to experience my own pain again, so that I can understand more of them and seek to find a way to alleviate their suffering in some small way.

You can find out more about my perspective on Sympathy, Empathy, Compassion, and Altruism in my post.

Bad Labels

The research on labeling, and how the labels that we apply to others and to ourselves shapes our behavior in subtle but persistent ways, is well-replicated. When students are labeled bad by their teacher (or administration), they do more poorly. When people label themselves as stupid, dumb, or incapable, they inevitably become this. (See Mindset for more on labeling.) Whether you believe that you can succeed or that you will surely fail, you’re right. However, you’re right not because of your skill, but rather because of the label that you apply to yourself.

One of the challenges with shame is the possibility that it will clue on to you your worst moments. Somehow your shame defines you by the moment that you were weak or at your worst and fails to recognize that this isn’t the whole picture. We are – none of us – one moment in time or one decision. We’re a series of good – and bad – decisions.

A healthy act of shame resistance is to resist being defined by our worst moments. We can – and should – acknowledge that it happened, that it was bad, make restitution, reform ourselves, and so on. I’m not minimizing the need to address the consequences of the action or inaction. Rather, we should not be defined by that moment. We should refuse to be labeled as a thief (and a no good) because of one incident. We shouldn’t label ourselves as insensitive when we missed the tear in the eye of a loved one. We can be compassionate and have times where we’ve lacked compassion.

Caregiving

It can be absolutely exhausting. Caring for another human being can take its physical toll on you. However, this feeling pales in comparison to the emotional exhaustion that many caregivers experience. The warm glow from the comments of friends fades, as you don’t have time for yourself and can’t make it to see them, because you’re too busy taking care of someone. The feeling of joy for being able to take care of someone when they need it is overtaken by bitterness and resentment, as you realize that you may be saving or helping their lives at the seeming expense of your own.

Slowly, the thought creeps in. What would it be like if this person died? What if I didn’t have to sacrifice my life for theirs any longer? And the thought starts to linger longer and longer. However, the thought itself seems shameful. What kind of a monster am I? What kind of a person would want someone they loved to die just so they can spend more time with friends? Why can’t I just suck it up and accept my fate?

The problem is that this perspective – shame – fails to realize that this is a normal response to exhaustion. The conclusion isn’t the right one, but the path that’s being walked makes sense. It’s a sign that you’re overburdened – not that you’re a monster. However, shame won’t let you see this. You’re supposed to be the perfect father or mother or relative. You’re supposed to be able to handle this on your own. You don’t need tights and a cape, but you’re supposed to be super.

If you’re in this situation, I know it’s tough. The difficult challenge is how to get the support you need to not become exhausted. It’s difficult when your siblings won’t help to take care of your aging parents and refuse to find them care, because it’s too expensive. They want to control the decision making – or influence it – but they’re unwilling to come support you while you’re supporting your parents. The answer – though it’s hard – is to stand your ground and insist that you need to be able to take care of yourself, your family, and your life too.

Peak Perfection

I’m always amazed at how put together other people appear. Whether it’s your favorite musician or the TV star or the celebrity, it seems like their life is right. From the outside looking in, everything seems perfect – until it isn’t. It takes a toll. Projecting the image that you’re perfect when you’re not is hard. You’re always considering what you have to say and where you need to be, what you need to wear, and what you need to drive.

It’s exhausting. It’s exhausting to believe that you must be put together. It’s hard to hide the gambling addiction or the liver problems caused by drinking too much too often. Preachers hide their marital trouble from the congregation. Politicians hide their financial problems from their constituents. The mayor is worried how long it will be until the town finds out about how much he’s been drinking.

Perfection takes work – and a bit of careful editing. How many takes happen before your favorite action thriller’s scene is done correctly? Two or three? Or thirty? How much work is put into hiding the mistakes and making the best take seem perfect? It’s not reality that anyone’s perfect. No one can be perfect, but in our highly edited society, we believe that it’s possible.

The problem is that no one has that kind of energy. No one can be all things to all people at all times. If we’re unable to allow ourselves to be real and vulnerable, then we’ll end up feeling lonely inside and shame has won. We silently condemn ourselves for not reaching the perfection we seek without consciously realizing that it’s an impossible goal.

Need for Learning

The understanding that perfection is an illusion isn’t an opportunity to sit back and do nothing. We need to learn from our mistakes, and we need others who are willing to do the same. We need to find ways to grow that are real. We’re not trying to be perfect, but we’re striving to be better. One of the amazing things about humans, both individually and collectively, is our capacity to become more than what we are.

The best way to do this is to learn from our trials and failures. The more willing we’re able to stare into the places that we haven’t done well and examine what happened, the more we can figure out how to do better. We become the best possible version of ourselves through our learning.

Multifaceted

When you meet someone at work or in a community club or a kid’s activity, you associate them with that one thing that you know them for. However, everyone is more complex than the one view that we see them through. They’re more than the stereotypical soccer mom. They’re more than the corporate executive. Everyone of us has facets to our life that others don’t see. While it’s normal for us to seek to simplify other people into categories, it’s equally frustrating.

People need simple, but I spent my whole life building this complexity. For me, my interests are so diverse that people struggle to put me into a box. They don’t understand embedded systems programming and multithreaded technical detail with an interest in information architecture or psychology or user adoption. These facets of my personality – my me – seem incompatible. It’s frustrating to try to explain the interests and the passions and to have folks not understand.

People wonder how you get anything done with so many diverse interests. The question lingering in the minds of folks is how can both be true? How can all of it be true? I can tell them that the answer is hard work and dedication, but that’s not an answer that they can hear. It’s easier to find a single-dimensional view of others – of me – even if it minimizes others to cardboard cutouts, even if it means that you miss their richness.

Disconnected from Ourselves

The saddest thing about shame is the way that it disconnects us from ourselves. It causes us to focus on one facet of who we are, judge it, and disconnect with others, but we also lose the richness of our understanding of ourselves for the single-faceted focus. It seems like it should be easy to know yourself. It seems like you should be able to just know who you are, what you like, and what will make you happy. However, Daniel Gilbert points out in Stumbling on Happiness that we don’t know what will make us happy. Jonathan Haidt in The Happiness Hypothesis and Daniel Kahneman in Thinking, Fast and Slow point out that we’re not one commander at the helm of the ship of our lives, we’re two. We’re the emotional elephant with pattern recognition and the rational rider trying to justify and explain the decisions made by the elephant. Dan Aisley points out that we’re Predictably Irrational – but we don’t know it’s so. Eagleman shows us how our brains lie to us in Incognito.

All of this is to say that, though understanding ourselves may seem easy on the surface, it’s perhaps the hardest thing we’ll ever do – and the most rewarding.

Strength from Weakness

In the end, the way to conquer shame is to become weak. The path to victory runs through the forest of defeat. The way to connect is to realize that, even though I Thought It was Just Me, it isn’t.